Professor John Gillies

2021 UNE Distinguished Alumni Award Winner - Professor John Gillies

In recognition of his exceptional contribution to Literature and Film Studies and his innovative attempts to explore new topics and new ways of understanding English Renaissance literature.

The boy and the Bard

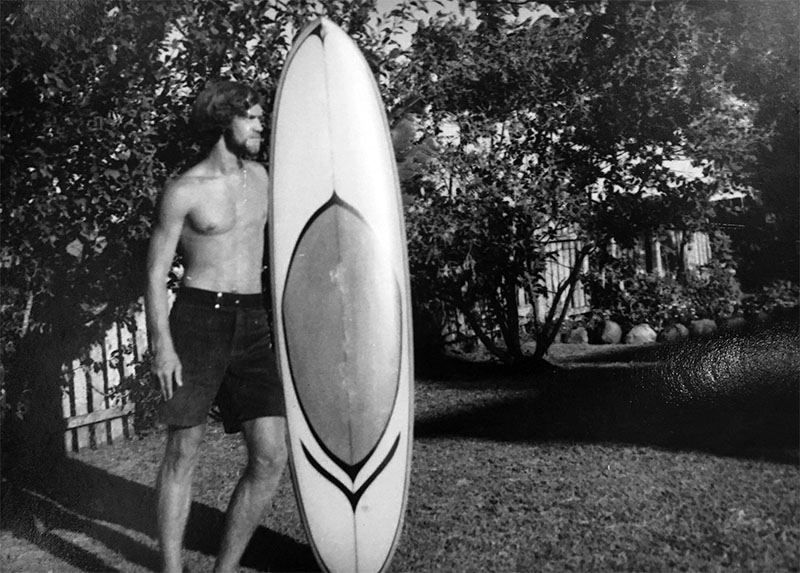

The young North Coast surfer who went on to become one of the world’s most eminent Shakespearean scholars reflects on his studies at UNE with the kind of detail and insight the Bard himself is renowned for.

Professor John Gillies - Paris, Place Dauphine

Professor John Gillies - Paris, Place Dauphine

Professor John Gillies, 2021 Distinguished Alumni Award winner and University of Essex luminary, has been based in the UK for the past 20 years, yet easily conjures up images of the day he arrived in Armidale in 1965 to begin his Bachelor of Arts degree.

“I vividly remember the drive up from Lismore with my parents,” John says. “The tablelands seemed less inviting than the coast. It was a slightly queasy experience – stepping out of the bubble you know into something strange and shapeless.”

Soon after eschewing Psychology and Sociology for a major in English Literature, John’s new world began to take shape.

“The curriculum then was everything from Beowulf to Border Country (Raymond Williams’s 1960 novel about escaping his own first bubble, in Wales),” John recalls. “Learning Anglo Saxon (from Dr. Elizabeth Liggins) was a revelation. It actually married up with my surfing. Anglo Saxon literature is full of sea voyaging, and I would gratefully compare the surf at Lennox Head to the ordeal of navigating the North Sea poorly dressed in winter. What I loved then was the sheer strangeness of that life-world: “the past is a foreign country, they do things differently there”.

A young John Gillies in his backyard with his surfboard

A young John Gillies in his backyard with his surfboard

A “helpful and hospitable” English department – “I remember all their names” – provided John with the coordinates to traverse this new terrain, and to go on to complete First Class Honours. “My first personal tutor, a patient Mr. Ian Grenfell, one day described literary research to me – to which my response was a bumptious: ‘what, you mean people actually do that?’,” John says.

Mentors were as illustrious as they were abundant – from visiting Oxford lecturer and Jane Austen specialist Mary Lascelles to Department Head Herbert Piper (a protégé of British writer C.S. Lewis). “I look back now and realise how good the classes and lecturers were,” John says. “I remember Bill Hoddinott, who went on to document local Aboriginal languages. All in all, I spent five years in Armidale (four for the BA Hons) and one (of two) for my Masters. After the third year, I moved out of Robb College into Armidale first, then to a house about twenty miles out of town, where I ate a lot of rabbit.”

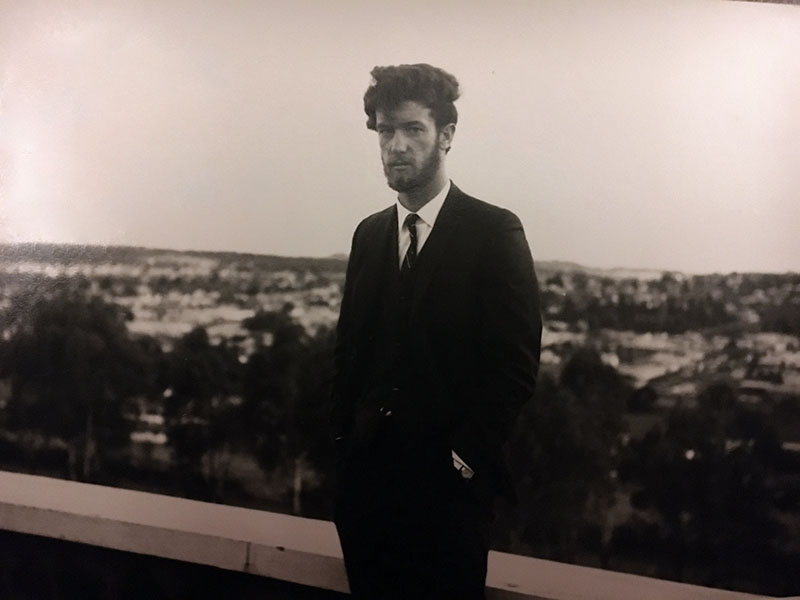

John Gillies at Armidale Lookout

John Gillies at Armidale Lookout

After a year in Melbourne, followed by another “on the run” in the outback as a conscientious objector to the Vietnam War, John got a job as a tutor in English at Macquarie University under Professor Piper when Gough Whitlam was swept to power and conscription abolished. “A few years later Professor Piper called me in and said that he couldn’t keep me on but could ‘get me into Oxford’, so I decided to do the Shakespeare Bachelor of Philosophy there,” John says.

A year at the Shakespeare Institute of the University of Birmingham was followed by two decades back working in Australian universities, before John returned to the UK in 2001, as Professor in Literature at the University of Essex. He’s been with the Department of Literature, Film and Theatre Studies ever since. But it was in Australia that he produced his seminal work Shakespeare and the Geography of Difference, which draws on cartography to explore Shakespeare’s imagination of the exotic world that spread far beyond Europe.

At Latrobe, John also researched Chinese Shakespeare adaptations of the 1980s that had been captured on priceless and fragile video. “This was the decade in which China was emerging from the Cultural Revolution,” he says. “As their performance style was mostly antiquated, the point of our collaborative project was to decode them and make them comprehensible to audiences who wouldn’t otherwise know what was going on.

“Such performances say something about being human that modern theatre just can’t say. Shakespeare’s imagined world is as historically remote as theirs, but he is modern, too. Through him they can escape their cultural ghetto.”

Professor Simon Palfrey, from the University of Oxford, describes the project as “a heroic act of imaginative resourcefulness and indeed political courage” and admires John for a career that is “courageously independent of fashions and envies”. “And, very unusually, he has never stopped questing,” he says. “John has influenced many thinkers of the highest calibre, young and old, in all corners of the globe.”

Beyond his many scholarly studies, lectures and ambitious projects, John continues to delight in Shakespeare’s influence and “uncanny powers of language”.

“If you are not religious, then words are the closest thing we have to immortality,” John says. “The important words have been alive for centuries, even millennia, and … it is a moot point whether we use them or they use us. When Shakespeare uses an important word, he seems to be on nodding terms with that extended life as well as the contemporary resonances. Hundreds of words and expressions wouldn’t be there but for him.

“Then there is the fact that Shakespeare has vitally influenced every cultural moment in England over the past four hundred years: all these periods are saturated in Shakespeare and vice versa. Shakespeare is a window onto every cultural moment through which he has passed. He is also a portal through which they have passed and been influenced in turn. This makes him a unique cultural phenomenon.

“From the eighteenth century, Shakespeare began to percolate into the European languages: German, then French, finally pretty well all of them (to say nothing of America). I will be giving a lecture in Poland next year. Gdansk has the remains of a theatre in which Shakespeare’s plays were performed during his lifetime, first in English then in German.”

So if his life were a Shakespearean play, which one would it be?

“It would have to be Hamlet,” John says, “not because I’m any kind of leading man, but because Hamlet wants to point the finger (at his step-father) but also feels hopelessly swamped in his own wrongfulness. Hamlet is obsessed by original sin. This leads to moral paralysis. Does he ever manage to break out, win some sort of moral victory at a tragic cost? The jury is still out.”

Leading man he may not be, but John continues to command the international stage. “He has a very rare historical and philosophical imagination,” says Professor Palfrey. “He is capable of seeing across cultures, divining relationships, whispers of affinity, where less sensitive minds would see only flat difference. In his work, as in his daily life, his percipient, compassionate mind is always rooted in the local, in the things as they are felt and lived.”