Gonzalo Perez del Castillo

2021 UNE Distinguished Alumni Award winner - Gonzalo Perez del Castillo

In recognition of his dedication to improving the circumstances of those disadvantaged by poverty, inequity and lack of access through his significant contribution to the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) in South America.

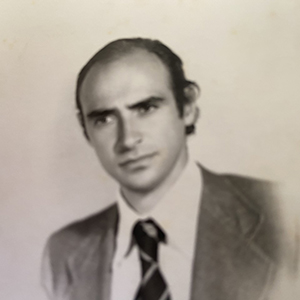

Gonzalo Perez del Castillo in the mid 70s

Gonzalo Perez del Castillo in the mid 70s

A true citizen of the world

During a prestigious 23-year United Nations career, Gonzalo Perez del Castillo worked as a senior officer in war-torn countries and under a number of repressive regimes. Later, as a senior consultant to the UN, he supported the recovery of Eastern European nations after decades of conflict, and he’s been responsible for countless successful development programs aimed at alleviating poverty and fostering social and economic prosperity in Third World countries.

Working in sensitive and politically fraught situations was commonplace for the respected international civil servant and now 2021 UNE Distinguished Alumni Award winner. However, the memories of Gonzalo’s 1980-4 UN Development Programme (UNDP) posting to Chile, at the time of former president Augusto Pinochet’s brutal dictatorship, remain with him.

“Pinochet was ruthless,” recalls Gonzalo. “Protests of any kind were repressed. There was no free press, and political opponents and union leaders had either been killed, imprisoned or exiled. Those that remained were under constant watch. If they stepped out of line, they would also be eliminated, imprisoned or exiled.”

It was an unwelcome place for an international organisation committed to upholding human rights.

“Declarations and accusations against the Pinochet regime were common in the UN General Assembly and other UN bodies and the regime was continuously sanctioned by the international community,” Gonzalo says. “The relationship with local UN representatives was therefore very tense. We received telephone insults and threats, occasionally even death threats. UN personnel felt it was our duty to stand up and protest and, within our limits, protect the people persecuted by the regime.”

Indeed, former colleague Carlos Mazal, now with the National Academy of Economics of Uruguay, remembers a leader of firm resolve and courage.

“I was Chief of Mission of the UN’s Intergovernmental Committee for Migration and they were difficult times, for Chilean citizens and both of us,” Carlos says. “Gonzalo never wavered in using the tools of the UN … to help directly or support my work of safeguarding the lives of those threatened by the secret services and death squads. He did not have to do it, but he did.”

The son of a diplomat, Gonzalo arrived in Australia from Uruguay at the age of 16, a “very weak and confused adolescent”, with no English and “totally inadequate schooling”. Tackling tertiary study was, literally, a nightmare. But the Australia of the 1960s was accepting and egalitarian, and studying Rural Science at UNE Gonzalo (better known as Pancho, after the Mexican tennis player of the time) found a sense of belonging. He enthusiastically played soccer and gave many a memorable performance in the end-of-year theatrical reviews. The experience opened his mind, inspired tolerance and adaptation, but also critical self-reflection. Australian values and codes of conduct also seeped into his psyche.

“UNE turned out to be a dream place for me,” he says. “It was a small university campus and the ambiance at Robb College made me feel at home. Nobody knew where Uruguay was and frankly nobody cared.

“What I learned in Australia, and particularly at UNE, accompanied me for the rest of my life. Men like Professor Bill McClymont, Dean of the Rural Science Faculty, Ben Meredith, Master of Robb College, and so many others left an indelible mark on me. But what I cherish the most are the Australian friends I left behind.”

In the decades that followed, the Australian notion of a “fair go” would influence Gonzalo’s approach to matters of international importance. After graduating, he returned, “22 and idealistic” to a Uruguay on the verge of civil war. The opportunity to join the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) was “a dream” and he slowly worked his way up from a junior professional post in Rome to positions of increasing responsibility. Eventually, Gonzalo was appointed UN Resident Coordinator in El Salvador, Belize and Bolivia, and lived in eight different countries, rich and poor, during field missions.

“This included places where most of the population never had a chance, no health or education, no means of communication or even affordable transport out of their village and their misery,” Gonzalo says. “In Australia, even the poorest migrants, who were prepared to work hard, had a bright future for themselves and their families. I laboured myself during the holidays to get some money, and no matter how humble the job was (like cleaning up manure in a pork farm near Armidale) I was always treated with respect.

“Although I have never returned to Australia, some Aussie attitudes have remained with me, especially the idea of a ‘fair go’. I often used “fair go!” in international meetings when people who had difficulties expressing themselves in English were being dismissed or interrupted. Some of my United Nations colleagues would occasionally say to me: ‘We need a bit of your Australian approach here’, so something evidently stuck.”

Many of those colleagues recall Gonzalo’s leadership during the civil war in El Salvador, when he was serving as UN Resident Coordinator (from 1987-1990) and negotiated what was then the largest UNDP aid program in history for the displaced population. In the midst of a guerrilla offensive, with half the country overrun and the capital under bombardment, Gonzalo had safely evacuated the family of UN staff and then staff members before the UN office was virtually destroyed.

Although he left full-time UN service in 1993 Gonzalo’s consultancy work since has commonly involved collaboration with the UNDP, international governments, inter-governmental agencies and NGOs. Anti-poverty initiatives, agriculture and trade, malaria treatments, democracy in Latin America and even reform of the UN itself have all come under his scrutiny.

Gonzalo Perez del Castillo

Gonzalo Perez del Castillo

Play scripts (first a bourgeois comedy, in 1973, and then a manifesto against dictatorships in Latin America, in 1976), poetry and novels echo Gonzalo’s adventurous exploits. His last book, Las Cartas Guardadas, published in 2021, is a love story set in a fictional country that “exposes the futility of the merciless ideological confrontation that has divided all Latin American countries and kept them in a state of dependence and underdevelopment until today”. A popular weekly radio program also gives Gonzalo the chance to continue reflecting on politics, international affairs and cultural issues.

“The UN is often attacked and my rivals say that I invariably defend it,” he says. “I am clearly still a UN militant and I always will be because the UN stands for values that I believe in – such as people have fundamental rights, regardless of their race, religious beliefs, gender or culture; that negotiation is always possible; and that war is the final and worst possible solution.”

The idealist that left UNE and Australia in 1968 has grown into a realist, but one who is no less passionate.

“All you need is love is not enough,” says the UN elder statesman. “As you move about the world, you need to observe and understand. And you need sensitivity. You need to live intensively and also to read and read and continue reading. A small minority of us are born into a very privileged situation compared to billions of others around the world. We should never forget that.”