UNE Tree Removal Program: an explainer

January 2018

What's happening to UNE's trees?

In mid-January 2018, the University of New England (UNE) announced that it would remove 78 trees that posed an unacceptably high health and safety risk to people and/or property. The decision prompted protests from some UNE staff, who have since been joined by others in the community.

As well as the aesthetic appeal of some of the trees marked for removal, which includes old eucalypts that may pre-date European arrival in the area, the protesters argue that the old trees contain hollows that provide nesting holes and shelter for wildlife. Such hollows typically only appear in trees at least 100 years old.

The protesters have proposed that alternatives to removal should be found for some trees. They have engaged in various forms of peaceful protest and lobbying as a platform for their case.

Why is the University persisting with tree removal and not looking at other solutions?

UNE acknowledges the environmental concern and personal sadness attached to the loss of old-growth trees. Those same concerns have motivated a long and extensive process of monitoring and remediation to try and preserve the trees.

However, having received expert advice that removal of 78 trees is the best option to ensure the safety of people on the UNE campus, the University has a duty to keep the campus safe and act on that advice as swiftly as possible.

Of the 78 trees identified as still posing a risk in 2017, 16 trees have since fallen of their own accord.

Update 23 January:

- A tree on Workshop Road that was to be removed has instead been lopped because an illegally parked car made felling impossible;

- A tree on the western campus that was to be removed was instead pruned of deadwood after parrots were seen to be nesting in hollows.

- A tree at Earle Page college that was not scheduled for removal was removed after a lightning strike last week badly damaged it. Another lightning-struck tree on the Sports Union road is being assessed.

How was the decision made to remove the trees?

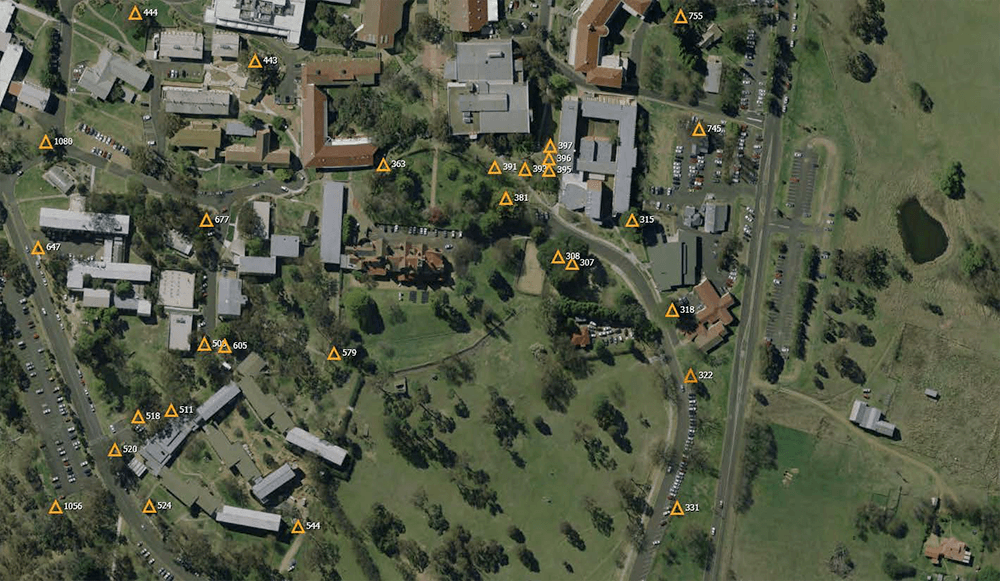

Since 2014, 5800 individually numbered trees have been monitored across the UNE campus by ArborSafe. This company performs a similar service for many university campuses across Australia.

Since 2014, 5800 individually numbered trees have been monitored across the UNE campus by ArborSafe. This company performs a similar service for many university campuses across Australia.

More than 100 trees of the 5800 were identified in 2014 as posing a risk. These trees are reaching the end of their natural life, have been damaged by pests or disease, or have grown or been pruned in ways that makes them vulnerable to failure.

Various forms of remedial action, like lopping and pruning, were begun in 2014 an effort to either save the unsafe trees, or leave them as “habitat stags” — trees that are severely trimmed of growth but leaving a firm trunk and safe limbs containing habitat holes. Removal was only considered as a last resort.

In 2017, the arborists found that 78 trees continued to pose a risk despite remedial work, and recommended that the University remove them.

How thorough was the assessment? How certain can we be that the trees really posed a risk?

AborSafe used five arborists to conduct its survey of UNE’s trees. Four hold Level 5 Australian Qualification Framework (AQF) qualifications, which is the qualification required of tree contractors by municipal councils. The senior consulting arborist holds Level 8 AQF qualifications, the highest Australian arboricultural qualification attainable.

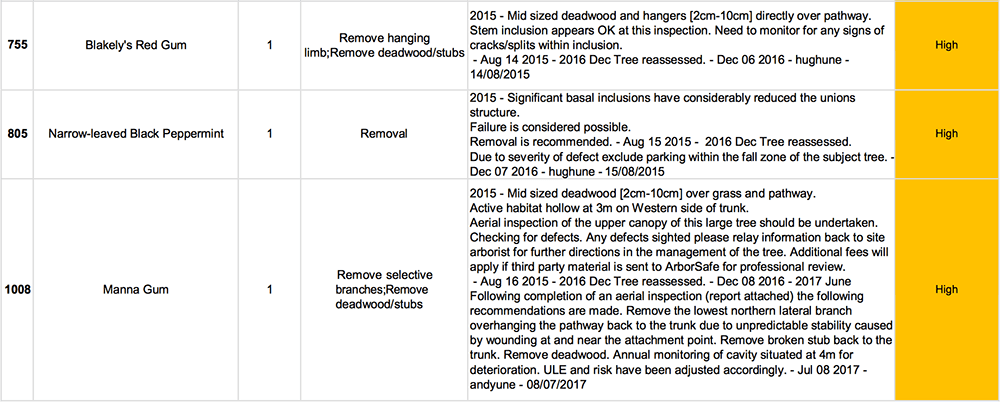

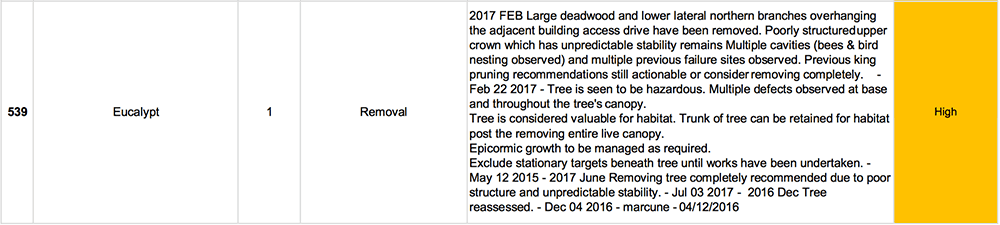

Since being identified as “at risk” in 2014, the 78 trees were monitored by close visual assessment and with tree-scanning technology. Where feasible, arborists climbed into the trees to examine evidence of age and disease. Aerial examination was undertaken in some cases, and in others the PiCUS Sonic Tomograph was used. This measures the thickness of the residual trunk wall and the presence of internal defects such as cavities or decay.

Those trees that have been felled show evidence of cavities and disease that bear out the arborists’ assessment.

Cross section of trees felled after being assessed as being at high risk of failure

Was a wildlife survey conducted of trees marked for removal?

Trees capable of providing wildlife habitat were recognised as such in the consultant arborists’ assessments.

UNE stipulated in its tender documents that crews removing trees must check for wildlife in the trees being removed and relocate any animals it finds, where practical.

Will the University consider alternatives to removal?

Over three years of monitoring, the consultant arborists reviewed the possibility of retaining certain trees as trimmed-down “habitat stags” or excluding traffic beneath them. In some cases measures have been taken to form an exclusion zone, but the trees scheduled for removal were ultimately deemed too unsafe even for this purpose.

The possibility of establishing exclusion zones through plantings, signs or physical barriers has also been considered.

This solution is complicated because the trees are on a campus densely occupied by buildings, roads, footpaths and other areas of traffic.

There is no regulation regarding permanent safe exclusion zones for unsafe trees. However, the Safework NSW Amenity Tree Industry Code of Practice and Safework Australia Guide To Managing Risks Of Tree Trimming and Removal Work are regarded as the minimum standard by the NSW Education Department.

According to these guides, an exclusion zone must be maintained around unsafe trees at a minimum distance of two tree lengths in all directions from the base of the tree.

For all the trees of interest, this exclusion zone intersects with built infrastructure or an area traversed by human traffic.

Preserving these trees would involve moving built infrastructure out of exclusion zones, and finding a satisfactory way of permanently excluding people from the danger zone.

With the exception of a permanent barrier like a high fence, the University cannot form an exclusion area that would guarantee people did not enter the fall zone.

Any death or injury caused by a high-risk tree would open up questions as to why UNE did not act on the advice to remove the tree.

Why did UNE not consult experts on its own staff?

It is essential for a public entity like UNE that the advice it receives is from an organisation backed by warranties and public indemnity insurance. Internal advice from University staff will not carry this necessary underwriting.

However, the University acknowledges that it could have usefully consulted with staff on an unofficial basis.

To ensure staff are fully informed and engaged with future tree removals — and more removals will be inevitable — the Chief Operating Officer, Professor Peter Creamer, has determined that a UNE Landscape Consultative Committee will be in place by mid-February 2018.

The committee will be made up of expert academic and research staff. Its work will be to provide advice to help inform management decisions affecting the University’s natural landscape. That advice will be incorporated into planning to help shape research and the ecological, cultural, aesthetic and utility values of the UNE campus for future generations.

In addition, the University is proposing to fund up to four higher degree (PhD or Research Masters) research project stipends in 2018 to support better understanding of the ecological role of old native trees.

The stipends will help students investigate questions like:

- How important are old remnant trees as a seed source for local regeneration?

- What does the trees’ population genetics tell us about their conservation?

- What birds, mammals and other animals are dependent on those trees?

- What is the role of these trees in the local pollination network?

The research may also improve understanding of isolated paddock trees, and their ecological function above and below ground.

What’s being done about replacing the trees that are removed?

UNE has determined that 500 native trees and shrubs will be planted in groves and corridors to replace the habitat and aesthetic values lost with the removal of 78 older trees.

The provenance and mix of those plantings will be determined in consultation with expert academic and research staff through the UNE Landscape Consultative Committee.

The decision to remove the trees was only communicated to staff at the last minute, and gave those concerned about the process little time to make their case against removal. What is being done to prevent a repeat incident?

UNE acknowledges that in hindsight, it could have improved communication around the process.

By establishing the UNE Landscape Consultative Committee, supporting targeted higher degree research and reviewing internal communication processes, UNE is working to more closely include the University academic and research community in future tree removals.