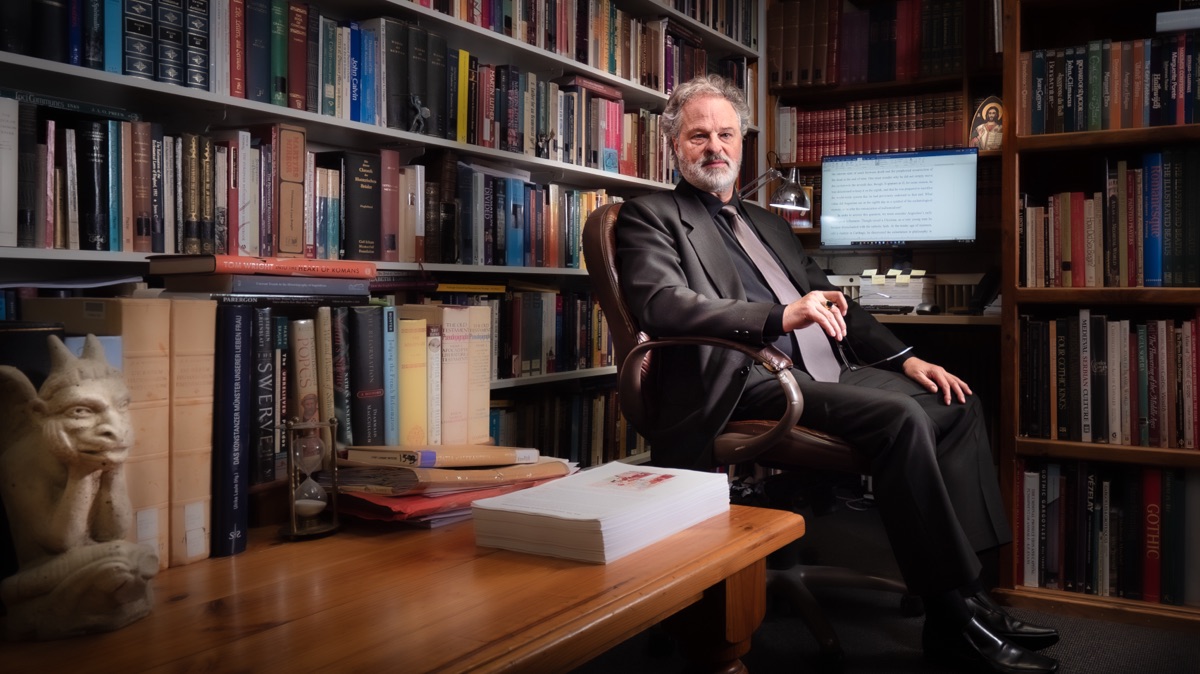

When UNE historian Professor Thomas Fudge began questioning signs of discontent within Armidale's Anglican diocese, he found a story that would take him 860 pages to document.

The resulting book, Darkness: The Conversion of Anglican Armidale 1960-2019, tells how the Armidale diocese, which practiced a traditional form of High Anglicanism, became strongly evangelical despite opposition from incumbent clergy and laity.

Professor Fudge interviewed 255 people and combed through long-buried documents to build a narrative that spans nearly 60 years. UNE Communications spoke to him about how a historian whose speciality is the Medieval period became so deeply engaged in local church politics.

Professor Fudge's book will be launched at UNE's Oorala Centre on 9 April, 2024. Launch details

UNE Communications: How did you become interested in this story?

Professor Fudge: I was asked to give a lecture on the occasion of the 125th anniversary of the founding of St Mary’s Anglican Church, West Armidale. That was straightforward but the organisers asked me to consider saying something about the uniqueness of St Mary’s. I looked into it. The book was the result.

Your specialities lie in different times and different places. How does this issue fit into your wider body of work?

I am a medievalist specifically but an historian of Christianity more generally. I am especially interested in heresy, dissent, those who take a different view, those who challenge authority structures, those who do not or cannot follow the well-worn path of the majority but who seek out new paths and new or different ways of understanding the world, faith, or religious practice. I recently showed a feature film to a group of students during an Intensive Residential School. It was about the famous philosopher and mathematician Hypatia who was active in the late fourth and early fifth centuries at Alexandria. The key line from the film has Hypatia saying to a bishop: “You do not question what you believe. You cannot. I must.” She was murdered by a mob of Christian fanatics. I am deeply committed to understanding the other side of religious beliefs and practices.

Why expend so much effort on what appears to be a localised controversy?

My mother always told me: “If you are going to do something, do it right.” That is, do it thoroughly. I have tried to make that a governing principle in teaching, research or administration. All of the controversies I have investigated as an historian began as localised issues. The history of Anglican Armidale has broader implications than this diocese. There are issues for the national church; indeed for Anglicanism globally. There are those who would argue that the issues that convulsed Armidale are central to the Christian faith. If this be true, then the book is not limited to an insignificant town in regional Australia. A local event can morph into much broader dimensions.

When it became known that you were researching this book, what was the response from the diocese, and from Anglicans not affiliated with the diocese?

Many clergy and laity here were happy to reflect on their histories, knowledge, experiences, and understanding of what had transpired since the early 1960s. There were only a handful of people who declined to be interviewed. There were different reasons for this: Some did not wish to revisit a painful past. Others were too afraid and were discouraged from speaking to me by their local ministers Many were grateful for the effort of recovering and reconstructing the other side which was in danger of being lost to history. I do not think there was a diocesan response, per se. The bishop was suspicious and said so. He claimed he respected me but did not trust me. I sought out prominent men and women from outside the diocese to try and ascertain how Armidale and its leading figures had been regarded from the 1960s down to the present.

Did you encounter obstacles in conducting your research?

The chief obstacle was the unwillingness of the bishop to allow unrestricted research. For example, the important diaries of the former Dean of Armidale, Evan Wetherell, who served from 1960 to 1970, remained off limits. Early on, I determined the diocese only possessed about three dozen pages of this voluminous source. The reasons given for its embargo were not persuasive and I secured elsewhere the entire diary and papers amounting to about 1700 pages. A handful of key persons declined to be interviewed including the incumbent bishop and dean. Doubtlessly there are an indeterminate amount of materials under lock and key in the diocesan registry of which I know nothing. This reflects the culture of the church at present.

Was there any particular significance about the Armidale diocese that made it the target of a factional takeover?

Bishop Moyes was in the later stages of a very long episcopate – 35 years— when he began to allow Moore College-trained priests to come from Sydney into the Armidale diocese. Other bishops elsewhere were unwilling to adopt this practice. They feared the attitude and approach of many Moore College trained graduates who had been indoctrinated to imagine they alone possessed truth. They adopted a particular point of view that they advanced as divine revelation and according to many priests at the time assumed an “I’m right and you are wrong” philosophy that was alienating and offensive to many clergy and laity.

Where there any particular conditions that made the Armidale particularly susceptible to evangelism?

Bishop Moyes’ willingness to be inclusive and foster a polychrome church in the Armidale diocese where all people would be accepted and united in love and tolerance. Moyes was clear on this point. There was a general naivete amongst many people who assumed that the Moyes vision would continue to prevail but it declined and was actively subverted. There was an assumption that Moore College graduates would fit into prevailing norms but this proved to be an unreliable tenet. Even Bishop Moyes grew restless and told Francis James in 1959 that he worried about Moore College. His eleventh-hour reservations came too late.

How has the book been received?

The book has received a broad range of response from high praise to condemnation. On the former, I have seen reviews or received emails hailing the book as ‘monumental’ and a ‘great service to the Church.’ One claimed the book had ‘pioneering importance in the history of Anglicanism.’ Some evangelicals have praised the book ‘as fair and even-handed.’ Another prominent evangelical cleric wrote to say: ‘The Anglican Church of Australia owes you its thanks.’ Naturally, there have been other, expected, responses. These include Rod Chiswell bishop of Armidale who effectively condemned the book before he read it. Dean Chris Brennan refused to allow the book to be launched on Anglican property noting the book was an assault on the church. An announcement of the book launch at St Mary’s, West Armidale during Palm Sunday worship notices was angrily denounced as ‘inappropriate’ by the Rev. John Cooper. Others feel the book is unnecessary and will detract from the important evangelical mission of the Anglican church. Some dioceses and Anglican bookshops have ordered the book by the carton. Sales have greatly exceeded expectation and interest is high.

Does this story have a wider relevance?

The story of the conversion of Anglican Armidale has wider relevance. The Sydney diocese sees itself as the guardian of truth and the custodian of authentic Anglicanism. Sydney (with some exceptions) has a missionary-oriented agenda which includes planting colonies of itself across Australia; in other words replicating Armidale. What Bishop Moyes failed to understand is that particular forms of Anglican religious faith cannot coexist. He naively believed that Anglo-Catholics, High Church traditions and conservative evangelicalism could work together in harmony. This was impossible in Armidale and is almost certainly impossible elsewhere without very strict safeguards put into place and carefully monitored. Moyes did not want a Sydney-style church in Armidale but that is what he ended up with. Bishop Rod Chiswell intends for Armidale to follow the example of Sydney and function as a training centre with an agenda to supply evangelical clergy to other Anglican dioceses across Australia. What happened in Armidale – in terms of doctrine, attitude and approach – will be attempted elsewhere. Darkness suggests probable outcomes. Anglican church clergy and laity should read the book to decide if what occurred in Armidale would be good for their church. Light or darkness? Readers should decide.

Your next project?

My ongoing research projects will take me back to my medieval heretics in Hussite Bohemia, an examination of the relation between Martin Luther and Jan Hus (a Czech priest burned for heresy in 1415) and maybe more on the Anglican church in Australia. I’ve been offered box loads of material!