When our postgraduate students formally graduate, they and their family and friends are not the only ones celebrating. Sharing in the excitement are the students’ “academic parents” – the supervisors who have ridden the highs and lows of this intensely personal journey with them.

“They are supervisors, but they become friends and mentors and colleagues,” says geologist and palaeontologist Marissa Betts. “They are your role models and the people you emulate.”

So a UNE graduation ceremony on December 9 was particularly thrilling for Marissa, as she watched the first of the students she has supervised – Stephanie Richter Stretton – receive her Bachelor of Science (Honours), with the University Medal. “I bought my own academic robes especially for the occasion,” says Marissa.

Also proudly watching on was Steph’s co-supervisor, Professor of Earth Sciences John Paterson – another branch in the young graduate’s “academic tree”.

“It’s an organic process, the transfer of wisdom and knowledge from supervisor to student, and this happens down the line,” says Honorary Professor of Paleobiology at Macquarie University, Glenn Brock, who has supervised almost 50 postgraduate students, including John and Marissa. “It’s a little like scientific osmosis.”

“That’s how science works – you stand on the shoulders of giants,” says John. “And with that comes a lot of wisdom.”

Steph is the latest in a long line of UNE scholars now occupying a veritable academic forest. Here we trace her “lineage” back to Glenn and discover the scientific “DNA” they share.

That’s how science works – you stand on the shoulders of giants.

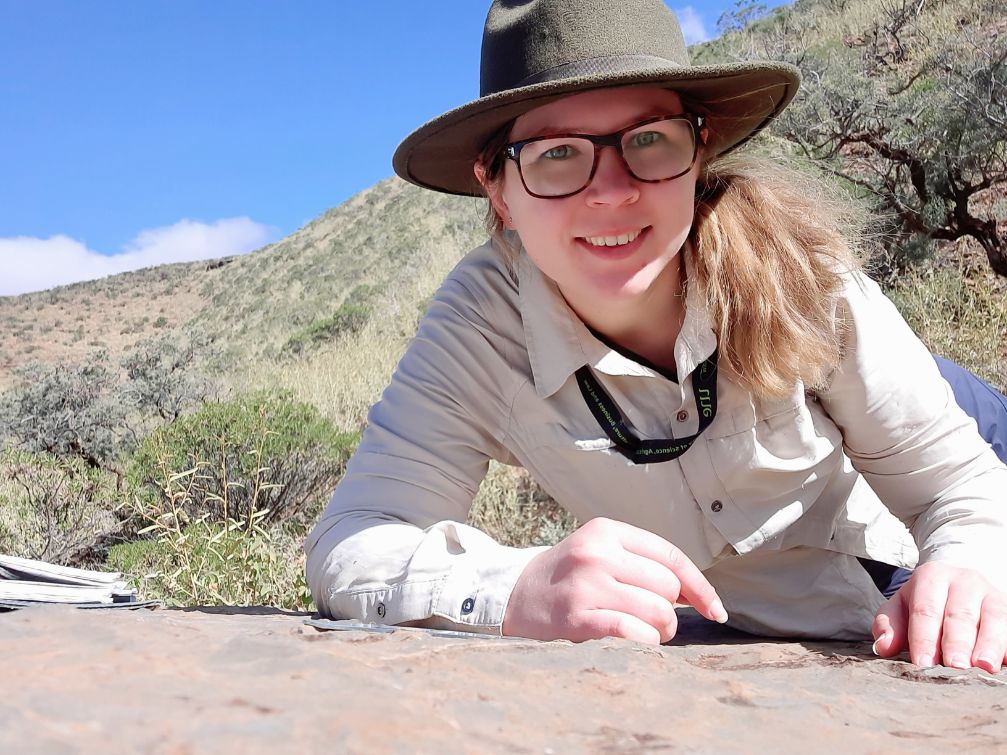

Steph checking out some fossiliferous limestone in the Flinders Ranges.

How do you describe the supervisor-student relationship?

Steph: I gravitated to Marissa because I felt she could understand my experience of working in palaeontology as a woman, and we both want to improve things for women working in STEM, particularly in geoscience. At times, our relationship has been very collegiate; at other times she and John have been reminding me to keep on track – I had a habit of going down research rabbit holes.

Marissa: It’s not just about training someone academically. You have to be there for them in all sorts of ways to get them over the finishing line. When I was a PhD student, I saw Glenn almost every day for three years. He created an atmosphere in the lab that made me feel safe and supported and welcome. As a supervisor myself, I can now help someone else through. I don’t have children of my own, but I think parents must feel like this – ‘Have I pushed them too hard?’, ‘Have I not pushed them enough?’, ‘Are they eating the right vegetables?’. I feel responsible.

I think parents must feel like this – ‘Have I pushed them too hard?’, ‘Have I not pushed them enough?’, ‘Are they eating the right vegetables?

John: Even at the PhD level, students need their hand held to some degree, so I’ve always sought to be hands-on. Two supervisors provide different expertise and perspectives, and ensure one is available to the student at all times. The different knowledge and skillsets really helps the student.

Steph and John at a GEOL311 intensive school, where John was the unit coordinator and Steph was demonstrating.

Glenn: I’ve always had an open-door policy, and your rapport with a student and level of trust builds up over time. It’s about the supervisor providing guidance but also inspiration and suggestions. I have always had my office in the lab, where all the students are. It fosters an informal but formal relationship, an inclusive environment in which students can speak their mind and feel they are taken seriously. I’m not a trained psychologist, but things happen in their lives and I lend an ear. You need to foster a balance between the academic side, which is why they are there, but also to build them as people.

Is gender an important consideration?

Steph: I see a lot of parallels between myself and Marissa. That’s why I think female role models are so important; I look at her and see that there is hope. I have learnt I am capable of a lot more than I thought I was. John has also been a rock and has provided a huge amount of support when Marissa hasn’t been around.

Marissa: The longer I stay in this field, the less diverse it becomes; they call it the leaky pipeline. So I feel I have a responsibility to support other women to cling in there. I think about that a lot, as well as the importance of maintaining good mental health. When you start out with your research project, you can’t know where your physical, emotional and spiritual limits are.

The new generation of academics are more switched on to gender bias.

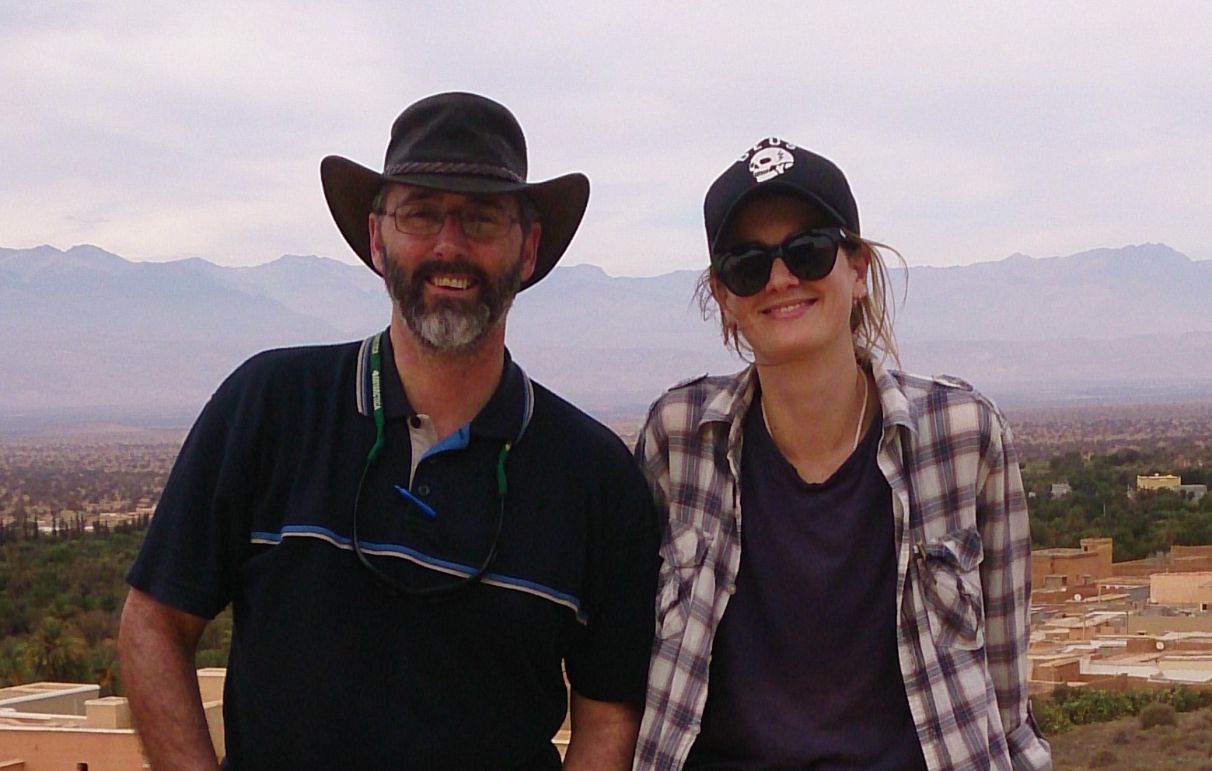

John and Glenn in the Flinders Ranges in 2016.

John: I think it’s critical for female students to have a female supervisor, but it’s equally important for male students to have a female supervisor, because it will teach them to be better, well-rounded academics. The new generation of academics are more switched on to gender bias. It’s one thing for someone like me to be aware of that and to teach the importance of inclusivity, but it’s not the same as Marissa giving her view as a woman researcher, because I’ve not been in her shoes. With Marissa, female students see someone living it and doing it.

Glenn: Wherever possible, it’s great for female students to have at least one female supervisor or mentor. At the time of Marissa’s research, we only had three male palaeos at Macquarie. But whatever the gender, the sexual proclivity, as long as the student was there to better themselves, I was always fully supportive. It’s about making sure they get the opportunities they need to thrive.

What did you appreciate most about your supervisor?

Steph: I could write a novel about Marissa. From an academic level, she is extremely knowledgeable and helpful and has been very giving of her time. I have never felt that I couldn’t approach her. There’s a huge personal component to writing a thesis, and Marissa gave me the encouragement and confidence to do it. John was truly my rock through this whole process – as he is for many in our department. He is incredibly calm and extremely good at reassuring anxious honours students. Some colleagues noted how stoic I was in the last few weeks of my thesis, and I found that strength through John. It wouldn’t be fair to not mention my “academic grandfather” Glenn – while I didn’t work closely with him, he is one of my palaeontology heroes and an infinite source of wisdom. I no longer recognise the Steph who started, in terms of confidence and navigating people, academic relationships and communications skills. Everything has come together.

Marissa: I had two great PhD supervisors in Glenn and John. Under Glenn’s tutelage, in his lab, I found a sense of community. I am trying to develop that family feeling here at UNE; a sense that everybody belongs. Because you can have as much love of the science as everyone else, but it’s people, not the science, that keeps you going. John was an amazing external supervisor, and is now a mentor, supporter and close colleague here at UNE. That we are now supervising students together shows that an academic family tree doesn’t always operate quite like a normal family tree!

If you get lucky and get a really good supervisor, chances are you’ll become a good supervisor yourself.

Glenn and Marissa in the field in Morocco in 2014, in the middle of Marissa's PhD.

Any final words?

Marissa: Every scholar needs a community of people to help them answer the questions they are interested in. We all become part of this diaspora, this huge network that will go on for generations. It’s the research questions that bind you, but it’s the emotional connection to the people you are working with, and the shared investment, that keeps you motivated.

John: The difference we saw in Steph from the beginning of her project to the end was amazing. She evolved from this very nervous individual to someone who was totally owning her work. Down the line, knowledge accumulates, and the style of supervision gets passed on, too. It’s like a parenting style; your supervisory style mimics that of your supervisors. If you get lucky and get a really good supervisor, chances are you’ll become a good supervisor yourself.

Glenn: I liked to take my students to overseas conferences to open their eyes, and these become foundational life events. Field work is the most important thing in palaeontology and networking with that greater palaeo community has borne great fruit for John and Marissa. That period of postgraduate study is such a beautiful time. You can learn so much that sets sail a great career.