2022 UNE Distinguished Alumni Award winner - Emeritus Professor Ronald Leng AO

In recognition of his significant contribution to agriculture in the area of ruminant nutrition and improving livestock productivity in developing countries.

For all the breakthroughs he’s made during his illustrious 60-year research career, Emeritus Professor Ron Leng recalls one achievement with particular pride. Of how some of the world’s poorest families benefitted directly from his science.

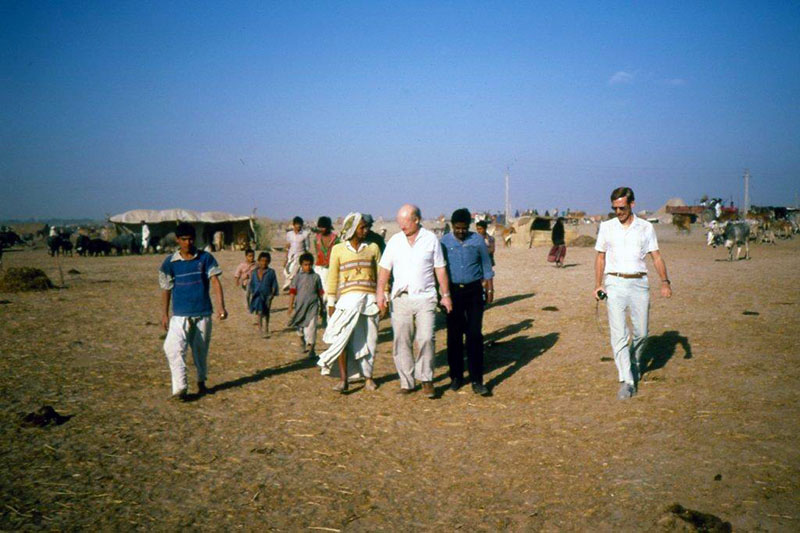

He had been visiting India regularly in the 1980s as a nutritional advisor to the National Dairy Development Board, trialling a strategy he and his UNE team had developed to optimise milk production in cattle and buffalo. Boosting reproduction rates and milk yields was key to advancing the nation’s infant dairy industry, and rural livelihoods, and molasses-urea nutrient blocks were showing great promise as a practical dietary supplement.

Within one or two years of introducing the blocks, Ron began noticing profound changes – to the village children.

“When we first arrived, the kids were typically snotty-nosed, but over time they began to look much healthier,”

“When we first arrived, the kids were typically snotty-nosed, but over time they began to look much healthier,” Ron recalls. “It turned out that the blocks had indeed increased milk production, the village women were feeding that extra milk to their babies, and it was helping the kids ward off disease. Healthy children was the best proof we could have that the cows were healthy, too.

"In certain villages in the Punjab - when I visited a village where the molasses-urea X blocks were successful - they made me ride through the village on horseback with Rita (my wife) following on foot. Rita didn't like it very much but went along with it, after all it is India, but she refused to hang on to the horse's tail."

"In certain villages in the Punjab - when I visited a village where the molasses-urea X blocks were successful - they made me ride through the village on horseback with Rita (my wife) following on foot. Rita didn't like it very much but went along with it, after all it is India, but she refused to hang on to the horse's tail."

“That way of using the blocks, which we called ‘the Armidale system’, ended up doubling milk yields (from extremely low to a respectable amount, which the women did not divulge to their husbands, fearing they might increase their liquor intake if they knew of the increased cashflow) and helping India to become self-sufficient in milk production. In subsequent years, the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations estimated that another 50 developing countries trialled the blocks, all initiated by this work. They had been used for decades in Australia before I came on the scene, but I put the blocks in places where they could have the most effect.”

Ron has gone on to work in almost 30 countries, applying research discoveries to production in some of the toughest of climates with the poorest of livestock feed. His earliest conclusions were no less valuable to Australian graziers still learning how best to manage their ruminants, to enhance growth, reproduction and the generation of milk and meat.

“The science of ruminants was still in its infancy when I arrived at UNE from Yorkshire in 1958,”

“The science of ruminants was still in its infancy when I arrived at UNE from Yorkshire in 1958,” Ron says. “But UNE was a leading light, with ecological agriculture giant Bill McClymont and internationally renowned biochemist Frank Annison commanding a strong reputation. It was a time in history when it was all breaking open.”

Initially working as a demonstrator in UNE’s Faculty of Rural Science while he completed his PhD, Ron was later awarded UNE’s first doctorate in Rural Science (in 1972) and became a powerful force through his own seminal research. He developed a major research school in ruminant nutrition and biochemistry, and managed research programs financed by the likes of the Wool Board, Australian Meat Research Council, and Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR).

In 1987 Ron founded the Institute of Biotechnology at UNE and, just five years later, the Centre for Duckweed Research and Development. He also became a founding member of the committee that successfully bid for the first of several subsequent Co-operative Research Centres (CRCs), for beef cattle and meat production.

All this activity attracted postgraduate students from across the world.

“Everybody was a migrant, just about; you were either a migrant from England or Australia, in terms of moving to this small, country town,” he says. “But everybody looked after each other. It was a very happy family in Armidale and quite a rambunctious place, to say the least. We built some great teams and did some great science, but we also had what I believe to be an essential component of my modus operandi, we had a lot of fun.

“I officially supervised 80 postgraduate students, plus others unofficially, and many have gone on to become leaders in the ruminant nutrition field. I think six or seven are now professors. My success, if you want to put it that way, is entirely due to the students who came to work with us. Ideas come to you when you have young minds around you.”

One of those scholars, adjunct with UNE’s School of Environmental and Rural Science John Nolan, recalls Ron’s inclusive, team-oriented approach, his “unbounded enthusiasm for scientific endeavour” and natural leadership qualities. “People quickly became comfortable in his presence, despite his formidable presence and reputation,” John says.

“Ron’s sometimes controversial hypotheses always kept a spotlight on his research activities and, at times, stimulated a climate for his competitors to carry out research that they hoped might prove him wrong. This demeanour also stimulated his many post-graduate students … and science has benefitted. Ron’s leadership created a golden era for UNE’s international scientific reputation.”

Emeritus Professor George Rothschild, an undergraduate contemporary of Ron’s, saw first-hand the international impact of many of the livestock-based programs Ron introduced while he served as head of the ACIAR from 1989-1995. “It highlighted not only Professor Leng’s high-quality research but additionally his capacity to forge strong partnerships with his counterparts from developing countries, and to mentor and train very many young scientists,” George says.

They were not alone. Equally important to Ron has been maintaining strong relationships with the grazing community he’s committed to helping. “Research is often very difficult to apply and you have to persevere with it to get people to adopt your findings,” says Ron, who has given countless seminars and workshops and authored highly popular books on feeding strategies. “I have always tried to respond to the needs of farmers and graziers, and to apply our science at the farm level.”

Ron Leng today in his garden

Ron Leng today in his garden

An Order of Australia recognised Ron’s contributions to agriculture and livestock productivity in 1993 and now his alma mater has, too, with a 2022 Distinguished Alumni award.

Since 1995 Ron has worked as an agricultural consultant, proving expertise to international aid projects, governments and feed manufacturers, and he continues to lecture and examine students enrolled in the University of Tropical Agriculture in Asia, which he helped establish in 1990.

“I’m 85 now, so I’m settling down a little bit,” Ron says.

Nevertheless, he has three new papers in production (to add to the 300 already published) and a book revision underway. Ron’s contributions to our understanding of methane emissions from livestock are also increasingly relevant.

“It is fitting that with the current challenges of climate change and the global commitment to move to net zero carbon targets within the next decades, Professor Leng’s expertise is now increasingly in demand through the requirements to reduce methane emissions from ruminants,” says Emeritus Professor George Rothschild. “This subject has formed a major part of his research over the past years and it is clear that he still has much to contribute.”