New research by an international team of palaeontologists has revealed stunning details of the skin that once covered the bodies of dinosaurs, and which fossilises much less frequently in comparison to bones.

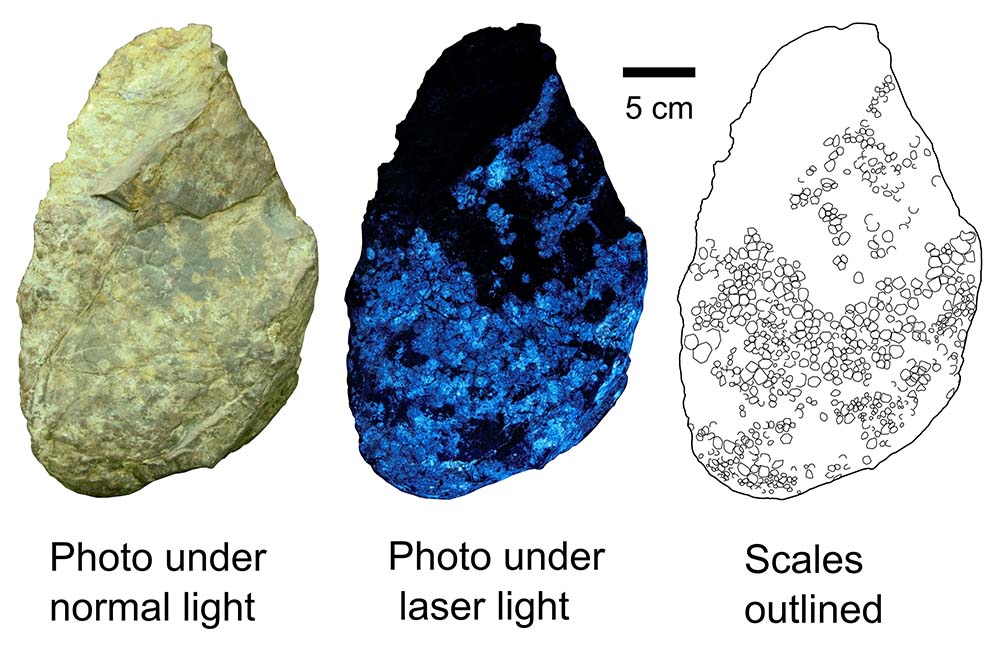

The study, published today in Communications Biology, uses sophisticated laser-imaging to capture minute details on the surface of a block of rock that was first discovered in England in 1852, and accompanied the bones of a long-necked sauropod dinosaur called Haestasaurus becklesii. This block is historically significant as it provided 19th century scientists with the very first look at the scaly skin of a dinosaur. Now, laser-imaging has revealed additional regions of preserved skin that cover the block, which are not visible under normal light conditions.

Nathan Enriquez, a PhD student from the University of New England (UNE) in Australia, co-led the study alongside Dr Michael Pittman from the University of Hong Kong, as part of an international collaboration that also included other researchers from UNE, the Foundation for Scientific Advancement, and the University College London.

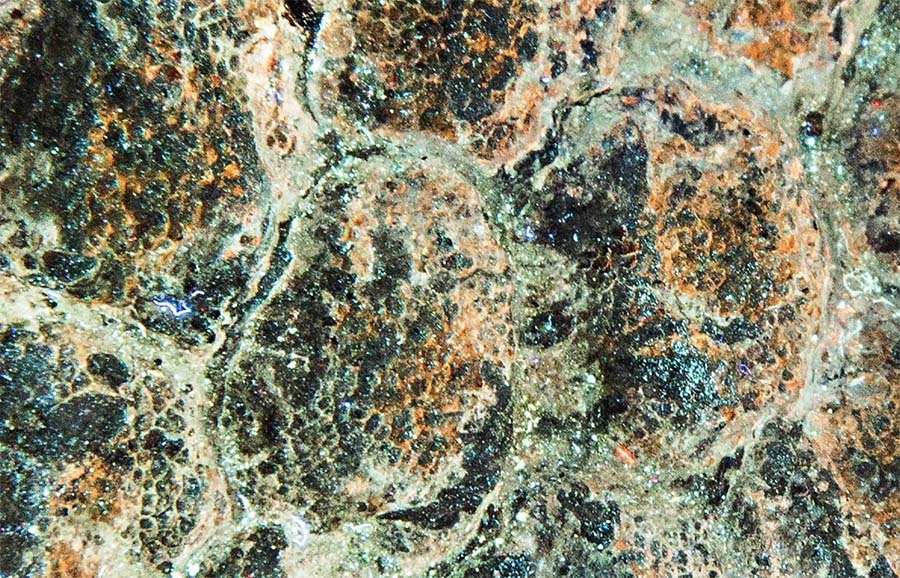

“Using this laser technology, we were able to identify small scales covering parts of the block that had never been seen before” Mr Enriquez said. “We were also able to observe the presence of small goosebump-like protrusions on the scale surfaces, each about 1 millimetre in size, and which we refer to as papillae,” Mr Enriquez said.

Another fascinating piece in the story of their evolution seems to be emerging, and we are looking forward to testing these ideas further.

These papillae would have given the skin surface a fine bumpy texture. Furthermore, as papillae are present in Haestasaurus becklesii as well as a variety of other long-necked sauropod dinosaurs, the authors suggest that this feature of their skin probably evolved at least 182 million years ago, during the early Jurassic period.

“The papillae are not seen in the skin of other types of dinosaurs, so the question becomes, why are they present in sauropods?” Mr Enriquez said.

Both the timing of their evolution and their raised, domed appearance may yet shed light on this question. In comparison to a flat, smooth scale, the papillae of sauropod scales help to increase their overall surface area. This would be an advantage for an animal as large as a sauropod, as it creates a larger body surface for heat to be lost through.

“When you’re as large as a sauropod, which can exceed 30 metres in length and 50 tonnes in mass, overheating becomes a real concern simply because you have a comparatively small surface area compared to your volume. Sauropods started getting really big in the Early Jurassic, which is about the same time that we predict these skin papillae evolved within this group. Perhaps, then, there may be a link between the emergence of these papillae and the evolution of huge sauropod body sizes,” Mr Enriquez said.

For now, the exact purpose of the papillae remains unclear, but the researchers already have plans to continue their investigations.

“Another fascinating piece in the story of their evolution seems to be emerging, and we are looking forward to testing these ideas further."