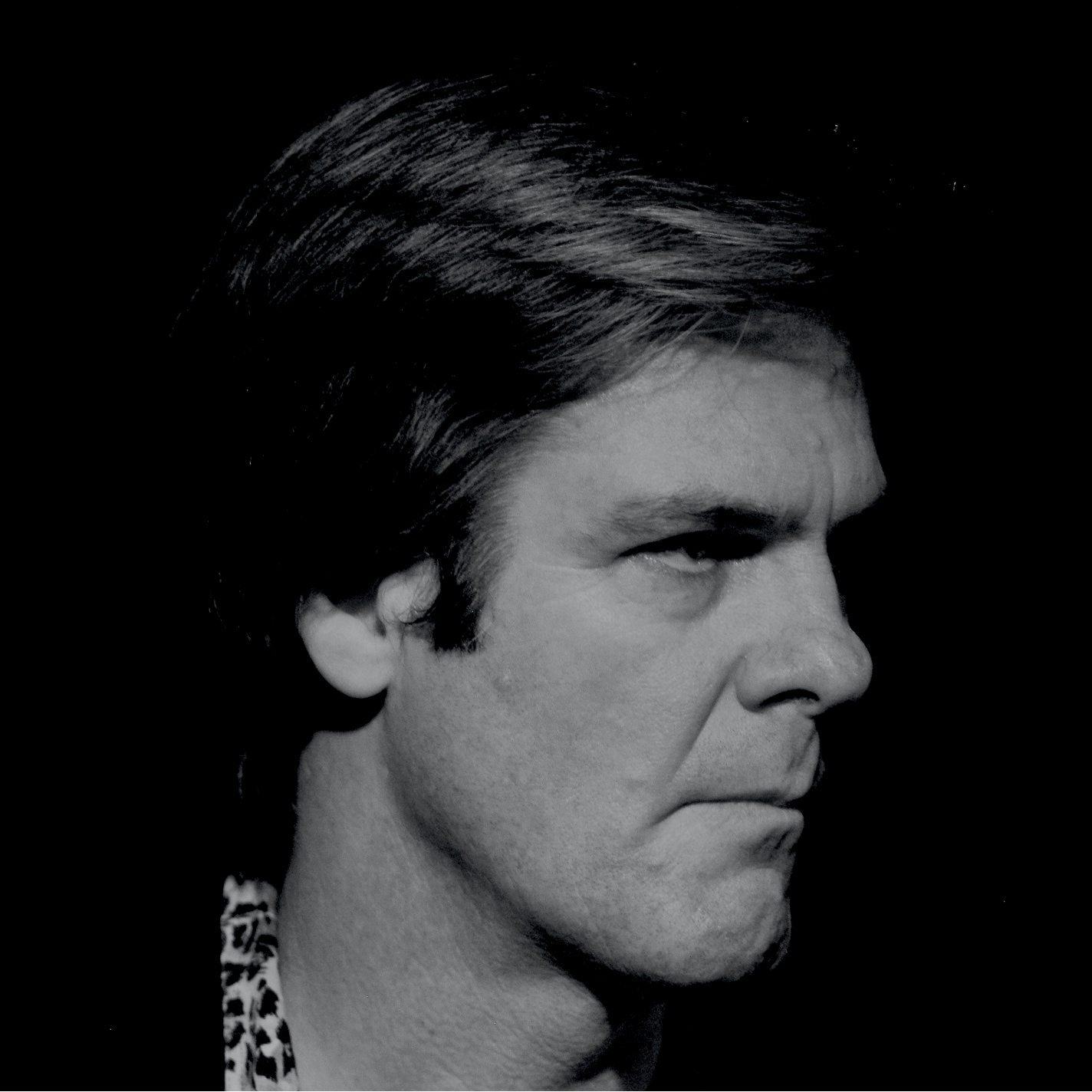

"I have lived, as everyone does, as a series of events," Don Walker told an interviewer last year. Those events are varied, and include studying science at the University of New England in the mid-1970s and working as a theoretical physicist in weapons research.

But it is his songwriting that Mr Walker is known for, and the reason he has been awarded an Honorary Doctorate by UNE.

He was a founding member of the band Cold Chisel, contributing vocals, playing keyboards, and becoming the writer whose songs lifted the band out of pubs into mythology. His lyrics, amplified into forceful anthems by the combined talents of Cold Chisel, were portraits of the casual Australia of the 1970s and early 80s that went beneath the apparent detachment of the laid-back Aussie to explore the emotions there.

Walker/Cold Chisel songs like Khe Sanh, Flame Trees, Cheap Wine and Choir Girl have since become the soundtrack to the period in which they were created. Cold Chisel’s performance of Walker's great Vietnam War anthem Khe Sanh was listed in the National Film and Sound Archive as being of "cultural, historical and aesthetic significance". Khe Sanh still gets hammered out at school formals by youth old enough to be conscripted, but with little idea of what the song refers to.

Mr Walker's lyrics pick up details that gather an entire place and time around them. He evokes the ceiling fan in a cheap room, listless youth around a pianola in a small-town pub, flame trees and canefields, the rankness of grievous hangovers and worse regrets. His lyrics often evoke a rural Australia that is still recognisable, although the pubs now tend to be smarter.

Cold Chisel described a tumultuous arc over a decade. When the band disbanded in 1983, Mr Walker took a five year break and then resumed writing, recording and performing, sometimes with himself in the spotlight, sometimes as the poet helping others give voice to themselves.

A one-off Cold Chisel reunion gig in 2009 led unexpectedly to the band's second life: its most recent tour was in early 2020.

In 2019, the Weekend Australian Review named Mr Walker as “Australia’s Greatest Songwriter”. His awards include the 2008 Country Work of the Year APRA Award win for "Everything's Going to be Alright", co-written with Troy Cassar-Daley; the 2012 Song of the Year APRA Award nomination for "All For You", performed by Cold Chisel; and the 2014 Blues and Roots Work of the Year APRA Award nomination for "Luck", co-written with Thomas Busby and performed by Busby Marou.

UNE's awarding of an Honorary Doctor of Letters honoris causa (HonDLitt) to Mr Walker for his services to contemporary music makes him the second UNE doctorate in his immediate family.

Born in Ayr, Queensland, to a farmer father and schoolteacher mother, he did most of his growing up in Grafton, NSW. He studied Physics at UNE in the early 1970s, while living at Robb College, earning first a Bachelor of Science and then his Honours degrees. Mr Walker wrote about his final weeks as a high schooler and his first encounter with UNE in his 2009 memoir, Shots:

In that final summer I’m locked in combat on fields and planes defined in arcane markings on the page, the study hours in a tiny sleepout off that stucco house single bed desk and piano, the love of the monastic calm when all the town is sleeping nestled across the night bend in the river, the gradual week-by-week tactical battles in the campaign, the setback then recasting of plans and the crawl back and advance beyond each small previous frontier tidemark to pass the final post exams. In the end the numbers come in a bale of city newspapers dumped on the cement out the front of that same bleak little poolhall cum beach corner shop across from the same deserted fairground of a caravan park as before.

What I pulled down is good enough to get me invited to take a look at a regional university campus, catching a bus two hundred miles into the mountains, half a day to get there. It ain’t like anything at home. The main administration building is a stone residence from the 19th century like you only see in pictures from England, a hundred rooms and levels and towers, with the original gravel coachways raking through gardens the size of the old farm. The air is crisp and perfumed, it’s really like that rackety old bus took me to heaven. Beyond the paths and flowerbeds are lecture halls, fifties blond wood panelling, new buildings full of old books, laboratories, dining rooms, recreation facilities, gymnasia and playing fields. I’m gathered on the lawns with a dozen others, goofy and strange and poorly dressed for the chill. They don’t say much, gawping round and smiling, nothing in common except razor minds, no knowledge of guns and floods and dirt-track hill climbs, and we get a quiet little welcome talk from someone, like we’re being petitioned to join an elect in some kind of beautiful in joke. Later that night I catch the bus back down the mountain, back to where money has to be earned and never enough.

Later, he invokes the sense of his divided loyalties as a student at Robb:

College, ten p.m., looking at work set weeks ago now due in eleven hours sitting in a pile I dumped earlier in the day on top of other stacks from other days. I’m thinking I’ll just wander down and watch the card school, and do that. The usual four or five are playing poker for low stakes, flaying each other and anyone who wanders in stupid enough to open their mouth with the kind of languid verbal wit that cuts a soul to confetti. I move on round the corridor, other open doors, circling back to my room thinking work now, leave the building instead and cross the courtyard and climb the stairs to a darkened common room, fold the covers back from the piano and send an hour of aimless meanderings chiming softly across thirty feet of empty parquetry in the cool as time ticks on, finally torn away by guilt and another night lost, back to my door, the piles of raw lecture notes untouched, set the alarm for five a.m. and crash.

Mr Walker was not the only member of his family to leave the river country for the mountains. His mother, Shirley, and sister Brenda also studied at the University. Shirley Walker won a University Medal, earned her doctorate, and became a senior lecturer in Australian literature at UNE, where she was the Founding Director of the Centre for Australian Language and Literature Studies.

UNE invited Mr Walker to reflect on a few questions.

What aspects of your own education (in the widest sense) shaped you most?

My formal education was in physics and maths. That encourages scepticism, and the avoidance of settled orthodoxies, which I think is positive. But any regimentation of a young mind has an equal downside.

Outside formal education, if you ever find yourself with very little, and find that you’re OK, that’s a valuable thing to learn.

What form of learning has had the greatest impact on you?

Failing.

Looking back at your student self, are you surprised at the directions that your life subsequently took?

Not really. I know how it all turned out, so far.

Are there principles that guided you that might also serve today's students?

I had principles that guided me, but I’m wary of suggesting guidance for others. How about this: Don’t trust anyone who demands compliance.

We tend to hear a lot about the challenges confronting humanity, but in most crises there is also opportunity. Do you think the world presents opportunities to those just stepping out into their post-student lives?

I just can’t impart “wisdom” to other people. I have my views about where things are headed, but that’s a lot longer and darker than a paragraph. I’m an optimist, and I think younger people will prevail, that’s all.