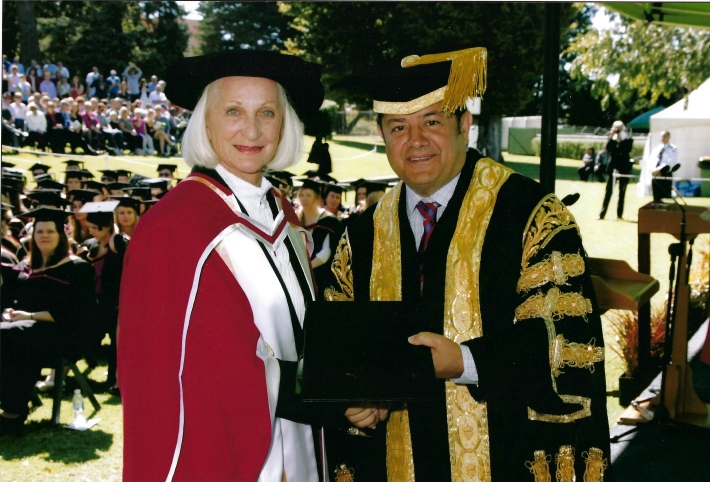

Now aged 87, Dorothy spent 12 years completing a Bachelor of Counselling, Honours, Masters and PhD studies at the University of New England, recently contributed to new federal health policy, and is now supervising a PhD student herself. And she has her beloved only child Chris to thank for inspiring the extraordinary journey.

Twenty-five years ago, at the age of 39, Chris suicided, leaving a 20-month-old son and pregnant partner. Dorothy had only recently lost her own husband to emphysema, and her father died soon after Chris. The compounding trauma saw her reach out to Lifeline, where she "found a new family to belong to" and began offering professional support herself, as a telephone counsellor.

"But after two years of telephone counselling I wanted to learn more about helping others and to study academically, and that's how I came to enrol at UNE," said the former accountant. "I knew what it was like to lose someone to suicide and I felt that was something I could contribute.

"It is a very different type of grief. After my son died, those people who wanted to help and support me didn't know how. That really is what prompted me to embark on my studies - to feed that lived experience sensitively into the field of suicide prevention."

Even today, Dorothy believes families can feel that there is a stigma attached to suicide. "Not that I ever felt ashamed of my son for the decision he made - I understood full well how much he was suffering before he died - but certain family members have never mentioned Chris's name in my presence since that day," Dorothy says. "A lot of people experience this. There are so many judgements made about suicide; the person is accused of being selfish and causing untold pain for their families."

Given Chris's family situation, Dorothy chose an Honours/Masters research project that was very close to her heart.

"I wanted to find out what could help my grandchildren," she said. "So I focused on researching the experience of people who have lost a parent to suicide as children. I am sure I approached it with the required academic distance, but the fact that I was suicide bereaved made an immediate connection with the people I was interviewing."

People of all ages and backgrounds willingly volunteered their stories. "I was so blessed, but that study alerted me to the fact that I needed to broaden the scope of the inquiry to look at the whole family experience of suicide, and that became my PhD," Dorothy said. "I then interviewed people who had lost a spouse, children, siblings and parents, and found that of all the people I interviewed, 50% had attempted suicide themselves. That's the flow-on effect. This has raised questions of whether there is some genetic predisposition or if they were following an example."

Exploring family histories of violence, addiction or dysfunction, going right back to grandparents, has led Dorothy to conclude that suicide pain reverberates through the generations. But far from being confronting, the experience has been comforting.

"It is the most healing thing I could have done, because I was connecting with people who had walked in my shoes," Dorothy said. "I didn't do the research for that reason, but that was the outcome. It gave others the opportunity to voice their experience and to feel that they, too, were contributing to the knowledge base on suicide bereavement and suicide prevention, that something positive was coming from their experience.

"The strongest feeling I had after my son died was that I was the only person in the world who felt the way I did. It was extremely isolating. Undertaking these two research projects helped me to feel that it is not in the least bit an uncommon story at all."

Ultimately, Dorothy hopes her (often cited) work informs those working in the fields of suicide prevention and bereavement, so that they might be more sensitive to the needs of those touched by suicide.

"People in the community commonly suggest putting it behind you, forgetting it ever happened and getting on with your life," Dorothy said. "But my research has shown that people who have lost someone to suicide long to speak their name, they long to talk about who they were and what they were like. That's what so many people don't understand. One of my greatest joys is when I meet someone who knew Chris and I can talk about him."