Landscapes of Production and Punishment Research

About the research

Convict Australia has been variously depicted as a place of brutality, repression and exploitation, or else a relatively free society where exiles enjoyed higher living standards and better life opportunities than the British and Irish labouring poor. This dichotomy is largely due to inadequate understandings of the landscapes of convict labour extraction.

Convict labour — varying contexts

The work that convicts performed — in greatly differing physical and administrative contexts — ranged from:

- highly skilled artisan craft

- industrial workshop production

- labour intensive manual work performed in irons.

Furthermore, while it is widely recognised that fluctuations in colonial labour demand and changing administrative practice are likely to have influenced the management of convicts, there is little understanding of the way this worked in practice, evolved over time, was expressed in the physical environment, or was representative of contemporary landscapes of free labour.

Explorative techniques

This interdisciplinary project uses innovative digital humanities and archaeological techniques to explore the physical impact of convict labour on both landscape and convict bodies. It integrates three exceptional longitudinal data series:

- The archaeological record for the Tasman Peninsula, including the UNESCO World Heritage listed sites of Port Arthur and the Coal Mines.

- Life course data for 12,000 convicts that served on the Peninsula (working in conjunction with the Founders and Survivors project).

- The administrative records generated as a result of forty-seven years of convict labour management.

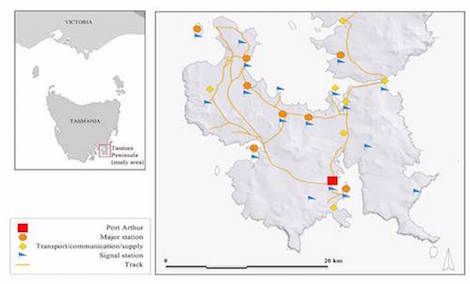

Fig.1: Map of the Tasman Peninsula, Tasmania, illustrating the location of major convict stations.

Fig.1: Map of the Tasman Peninsula, Tasmania, illustrating the location of major convict stations.

Historical records

1830 – 1877

Between 1830 and 1877, the Peninsula was a closed complex that covered all the major systemic touchstones in Australia’s convict experience: a repository for colonial offenders; a major hub for probation stations (1840–56); and a work-focused welfare establishment (1856–77). Across this period a large range of coordinated activities were carried out, from primary resource extraction to complex manufacturing, all linked to the sentencing and conduct of prisoners (Figure 1).

Port Arthur (1830–77) was the primary hub of manufacturing, ranging from artisan craftsmen, through various forms of industrial and manual labour, to the extremes of production while convicts were incarcerated in the ‘Separate’ (solitary) Prison. To this was added an increasing number of outstations providing materials and servicing transport, communication and security requirements.

Point Puer (1834–49) was an industrial reformatory and training school for juveniles, while the Coal Mines (1833–48) became a punishment station. The probation period witnessed a proliferation of new stations, each dedicated to an industrial activity such as timber-getting and agriculture, supplemented by a multitude of resource extraction operations including quarrying, brick-making, lime and charcoal-burning, and a miscellany of manufactory trades. From 1856, as the Peninsula’s workforce dwindled and retreated, Port Arthur underwent an industrial efflorescence as new technologies and administrative energies saw a surge in resource exploitation and manufacturing. No other place in Australia can claim such a span and diversity of convict industry and labour activity. In addition, the archaeological evidence appears to be at odds with the standard historical interpretation of penal stations as places of low-skilled, punishment-orientated labour exploitation.

It is time for the Peninsula to be reconsidered. We are testing the historical record against the density and diverse range of activity expressed in the archaeological landscape, structures and artefacts to fully explore the complexities of convict labour extraction processes.