Art-I-Facts Showcase

Portrait bust of Idia Iyoba (Queen-Mother)

MA1994.1.1

Collection: Africa.

Dimensions: H: 398.8mm, W: 153.6cm, D: 169.9mm.

Benin Kingdom, South-West Nigeria. 16th century AD.

Resin Replica: 20th century AD.

This is a cast portrait bust of Queen Idia, Iyoba (the Queen-Mother) of the 16th century AD Benin Kingdom of West Africa (South-West Nigeria). The portrait was commissioned by her son, Oba Esigiw, the King of Benin (AD 1504-1550) to commemorate the key role she played in his successful military campaigns against the neighbouring kingdom of Igala. Idia enjoyed some of the privileges awarded to high-ranking male officials including the right to wear the coral bead crown and beaded collar, and to use male symbols of power like the ada and eben (ceremonial swords).

This portrait-bust shows Idia with naturalistic facial features, half-lowered, downcast eyes, wearing the high coral bead collar, and peaked ‘parrot’s beak’ hairstyle covered by an openwork coral bead net with pendant strings of coral at the sides and back. The pupils, two large vertical marks on the forehead, and four cicatrices (scarification marks) above each eyebrow were originally inlaid with iron.

These lost-wax cast brass portraits were made by the royal guild of brass casters of Edo (Benin City), and housed on the ancestral altars of the king’s palace and queen mother’s residence. UNEMA’s portrait-bust is a replica produced by the British Museum of the original brass portrait which is currently held in the British Museum (Af1897,1011.1).

In 1897 brass sculptures, coral, ivory, and wood artefacts were looted from the Benin royal palace by a punitive British expedition. That expedition inflicted great brutality on the kingdom of Benin in the name of eradicating barbarism and promoting civilisation. The majority of the looted artefacts were brought back to Britain where they were auctioned off to pay for the costs of the expedition. Most of the Benin bronzes were purchased or donated to museums in Germany and Britain, where they had an enormous impact on the development of modernism, and forced the West to acknowledge the sophistication of African Art and Culture.

Calls to repatriate the looted artefacts have been made since Nigeria gained independence in 1960, and significant repatriations have been made world-wide since 2015. In August 2022, the Restitution Study Group, an African-American slavery reparations activist group, raised a counter-claim against repatriating the Benin bronzes to Nigeria, which had profited from selling captives into the Atlantic slave market, and suggested that the descendants of enslaved Africans should enjoy co-ownership of the bronzes held in Western Museums. The controversy continues.

Credits: Dr Bronwyn Hopwood, November 2022.

References:

CCP Staff, ‘Restitution Study Group Unable to Stop Smithsonian’s Benin Returns,’ Cultural Property News, 10 October 2022 & 15 October Update, https://culturalpropertynews.org/restitution-study-group-files-suit-to-stop-smithsonians-benin-bronze-returns/#:~:text=The%20Restitution%20Study%20Group%2C%20a,thence%20to%20the%20Benin%20Kingdom.

Docherty, P., Blood and Bronze: The British Empire and the Sack of Benin, London 2021.

Dohlvik, C., ‘Museums and their Voices: a contemporary study of the Benin Bronzes,’ International Museum Studies, May 2006.

Frum, D., “Who Benefits when Western Museums Return Looted Art?” The Atlantic 14 September 2022, https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2022/10/benin-bronzes-nigeria-return-stolen-art/671245/

Greenfield, J., The Return of Cultural Treasures, CUP, Cambridge 2007.

Hicks, D., The Brutish Museums: The Benin Bronzes, Colonial Violence and Cultural Restitution, Pluto Press, London 2020.

Nevadomsky, J., "Art and Science in Benin Bronzes," African Arts 37.1 (2004) 1, 4, 86–88, 95–96.

Nevadomsky, J., "Casting in Contemporary Benin Art," African Arts 38.2 (2005) 66-96.

Phillips, B., LOOT: Britain and the Benin Bronzes, Oneworld Publications, 2022.

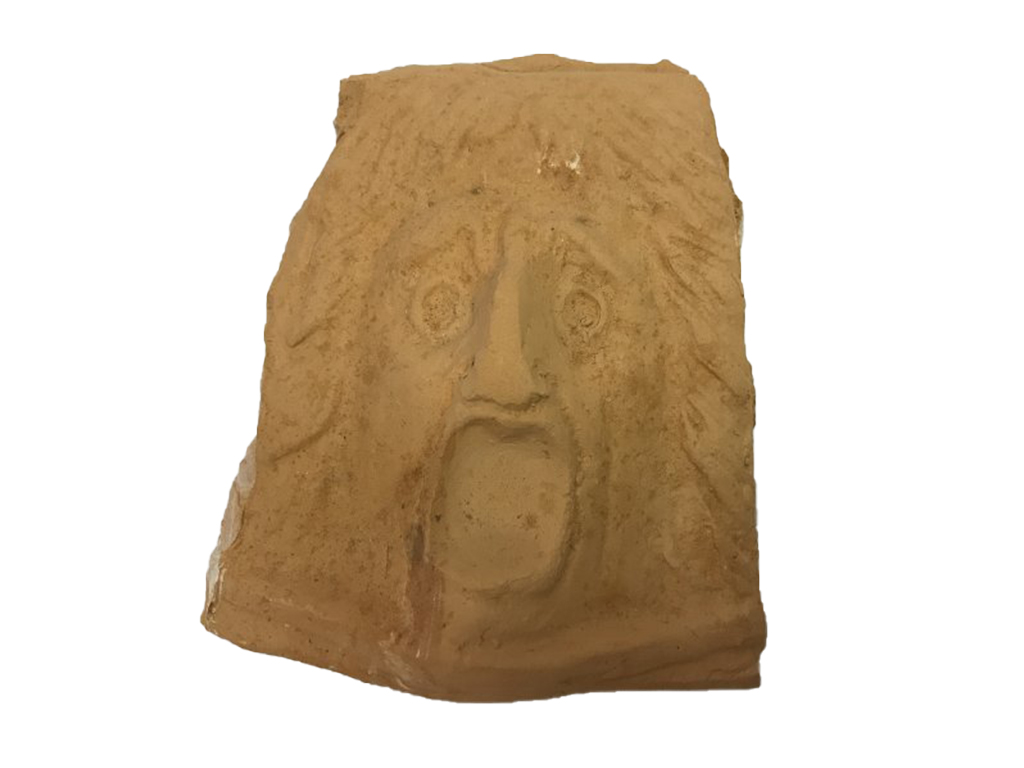

Past Artefacts showcases

Skull of Homo floresiensis (“The Hobbit” or “Flo”). MA2006.34.2 Ethnographic Collection: Asia. Special Collection: Homo Sapiens. Liang Bua Cave, Flores, Indonesia. Skull: 100,000-50,000 BP. Resin cast: 2006. Resin. On 2nd September 2003 a team of Australian and Indonesian archaeologists, led by UNE Professors Mike Moorewood and Peter Brown, found the remains of a small female hominin in Liang Bua Cave on the Indonesian Island of Flores. The almost complete skeleton of LB1, which stands just 1.06m tall, was named Homo floresiensis (nicknamed “The Hobbit”), and identified as a small species of archaic human believed to have inhabited Flores until 13,000 BP. The discovery generated instant controversy. Was the Hobbit really a separate species of human, the result of insular dwarfism, or a diseased modern human? Where did it originate from? and, Did it really coexist with modern humans until as late as 13,000 BP? Extensive work since 2003 has subsequently dated the Hobbit to c.100,000-60,000 BP with evidence of stone tool usage ranging from 190,000-50,000 BP. Since the original discovery, at least fifteen more partial skeletons have been discovered, and in 2017 it was concluded that H. floresiensis is indeed an early species of hominin, a sister species of H. habilis, and evidence of a very early and previously unknown migration out of Africa. The Hobbit is now thought to have gone extinct when modern humans reached the region c.50,000 BP. The LB1 Hobbit, now nicknamed “the little lady of Flores” or “Flo” for short, is the nearly complete skeleton of a 30 year old female. Her distinctive features are her small body and tiny cranial capacity. The skull of H. floresiensis housed a brain of just 380-417 cubic-centimeters (compared to the modern human brain of c.1400-1500 cc), and her body mass is estimated to have been just 25 kg. Flo’s wrist bones are similar to those of apes and Australopithecus, while her leg bones are more robust than those of modern humans, and her big toe is unusually short. When found, her skeleton was not fossilized but had the consistency of wet blotting paper, which required her bones to be left to dry before they could be completely excavated. Once excavated the skeleton was permanently housed at Jakarta’s National Research Centre of Archaeology. Only replicas of the skull and skeleton have been permitted to leave Indonesia. UNE has multiple replicas of the original skull created by the archaeological team and a full body with ceramic facial reconstruction created in 2008 by Dr Carol Lentfer. From 5-10pm on the 12-15 October 2022 The Hobbit is also appearing in the 2022 Parramatta Lanes Festival as part of a collaborative exhibition between UNE Sydney and UNEMA. The online version of the exhibition and interactive activities can be viewed here. Listen to this "Discover UNE" interview to meet UNE's Associate Professor Mark Moore, one of the original members of the archaeological team that discovered Homo floresiensis in 2003, and find out more about Archaeology at UNE. Credits: Dr Bronwyn Hopwood & Mark Moore, October 2022. References: Argue, D., Donlon, D., Groves, C., Wright, R., “Homo floresiensis: microcephalic, pygmoid, Australopithecus or Homo?” Journal of Human Evolution 51 (2006), 360–374. Argue, D., Morwood, M.J., Sutikna, T., Jatmiko, Saptomo, E.W., ”Homo floresiensis: a cladistic analysis,” Journal of Human Evolution 57 (2009) 623–639. Aziz, F., van den Bergh, G.D., Morwood, M.J., Hobbs, D.R., Collins, J., Jatmiko, and Kurniawan, I., “Excavations at Tangi Talo, central Flores, Indonesia,” in: Aziz, F., Morwood, M.J., & van den Bergh, G.D., eds., Palaeontology and Archaeology of the Soa Basin, Central Flores, Indonesia, Indonesian Geological Survey Institute, Bandung, 2009, pp. 41–58. Brown, P., & Maeda, T., “Liang Bua Homo floresiensis mandibles and mandibular teeth: a contribution to the comparative morphology of a new hominin species,” Journal of Human Evolution 57 (2009) 571–596. Brown, P., Sutikna, T., Morwood, M.J., Soejono, R.P., Jatmiko, Saptomo, E.W., Rokus Awe Due, “A new small-bodied hominin from the Late Pleistocene of Flores, Indonesia,” Nature 431 (2004) 1055–1061. Falk, D., Hildebolt, C., Smith, K., Morwood, M.J., Sutikna, T., Brown, P., Jatmiko, Saptomo, E.W., Brunsden, B., & Prior, F., “The brain of LB1, Homo floresiensis,” Science 308 (2005) 242–245. Falk, D., Hildebolt, C., Smith, K., Jungers, W., Larson, S., Morwood, M., Sutikna, T., Jatmiko, Wahyu Saptomo, & E., Prior, F., “The type specimen of Homo floresiensis (LB1) did not have Laron Syndrome,” American Journal of Physical Anthropology 140 (2009a) 52–63. Falk, D., Hildebolt, C., Smith, K., Morwood, M.J., Sutikna, T., Jatmiko, Saptomo, E.W., & Prior, F., “LB1’s virtual endocast, microcephaly and hominin brain evolution,” Journal of Human Evolution 57 (2009b) 597–607. Morwood, M.J., & van Oosterzee, P., The Discovery of the Hobbit: The Scientific Breakthrough that Changed the Face of Human History, Random House, Sydney 2007. Morwood, M.J., Brown, P., Sutikna, T., Jatmiko, Saptomo, E.W., Westaway, K.E., Roberts, R.G., Rokus Awe Due, Maeda, T., Wasisto, S., & Djubiantono, T., “Further evidence for small-bodied hominins from the Late Pleistocene of Flores, Indonesia,” Nature 437 (2005) 1012–1017. Morwood, M.J., O’Sullivan, P., Aziz, F., & Raza, A., “Fission track age of stone tools and fossils on the east Indonesian island of Flores,” Nature 392 (1998) 173–176. Morwood, M.J., Soejono, R.P., Roberts, R.G., Sutikna, T., Turney, C.S.M.,Westaway, K.E., Rink, W.J., Zhao, J.-x., van den Bergh, G.D., Rokus Awe Due, Hobbs, D.R., Moore, M.W., Bird, M.I., & Fifield, L.K., “Archaeology and age of a new hominin from Flores in eastern Indonesia,” Nature 431 (2004) 1087–1091. Large Plaque Amulet MA1978.8.1 Collection: Egypt. Dimensions: H: 24.4mm, W: 19.7mm, D: 10mm. Egypt. New Kingdom, 1560-1070 BC. Faience (?). This carved bifacial plaque from UNEMA’s Stewart Collection is an example of craftsmanship in miniature from Egypt’s New Kingdom. The images on the front of the plaque depict a feather, alongside the cartouche of a Pharoah (which is the king’s name written in hieroglyphs). The feather represents Maat, the principle of divine order maintained by the Pharoah. The image on the back of the plaque consists of two scorpions within a frame. The symmetry of the scorpions is a visually appealing design frequently found on ancient Egyptian artefacts. This plaque will primarily have been used as a stamp seal, but the inscription of a royal ruler’s name also allowed it to serve as a protective amulet. When pressed onto a piece of soft wax or clay, the carvings on the stamp seal will have created an impression. This impression or stamp could be placed over the closing mechanism of containers, such as a lid or string, as well as on tablets and documents in order to seal them closed. Stamp seals were usually made of steatite or faience, and occasionally materials such as metal or ivory. A blue or green glaze was sometimes applied to the surface of faience and steatite stamp seals to prevent wear and tear. Seal impressions were used for administrative purposes, to certify and safeguard the contents of containers, and to identify owners. Egypt adopted the practice of using seals from the Near East in about 3400 BC. The earliest seals were created using engraved cylinders, which were rolled over the clay to create an impression. These cylinder seals prevailed until the late Old Kingdom, when in about 2200 BC the more efficient stamp seal was developed. The craftsmanship of the carved designs found on seals peaked in the Middle Kingdom, along with the variety of stamp shapes available, including the popular amulet scarab. The price of seals was determined by their size, material, and quality of workmanship. Large, finely crafted seals were high status possessions. Seals were often worn as personal accessories. They were pierced for wearing on a string, or as bezels in the highly popular metal rings of the New Kingdom period. The perforations in the top and bottom of UNEMA’s plaque, in conjunction with its New Kingdom date, suggests it may have been part of a ring, although the object to which it was originally attached has not survived. Rectangular Egyptian plaque seals dating to the 14th century BC have been recovered from tombs in Egypt, Israel, and Palestine. The wide distribution of these seals in antiquity is the result of ancient patterns of trade and immigration. Credits: Dr Bronwyn Hopwood & Bronwyn Muller, August 2022. References: G.A.R. & N.F.W., ‘The art of seal carving in Egypt in the Middle Kingdom,’ Bulletin of the Museum of Fine Arts, 28.167 (1930) 47-55. Brandl, B., ‘Scarabs, seals, an amulet and a pendant,’ Bronze and Iron Age tombs at Tell Beit Mirsim, 23 (2004) 123-188. Sparavigna, A.C., ‘The symmetries of the icons on ancient seals,’ International Journal of Sciences, 2.8 (2013) 14-20. Sparavigna, A.C., ‘Ancient Egyptian Seals and Scarabs,’ SSRN Electronic Journal, (2016) 1-52. Ward, W.A., ‘A new reference work on seal-amulets,’ Journal of the American Oriental Society, 117.4 (1997) 673-679. Wegner, J., ‘The evolution of ancient Egyptian seals and sealing systems,’ in Ameri, M., Costello, S.K., Jamison, G., & Scott, S.J., eds., Seals and Sealing in the Ancient World, Cambridge 2018. Attic Red Figure Plate MA2005.6.1 Collection: Greek. Dimensions: diam. 187mm. Greece. 460 century BC. Terracotta. The central tondo of this Attic red-figure plate depicts a maiden wearing a sakkos and himation, pouring a libation from a trefoil-lipped oinochoe onto a rectangular altar. The black slip has been applied to the plate leaving two close-set red lines encircling the tondo, with a further red line appearing at the base and upper edge of the plate’s concave rim. The underside of the ring base is moulded with bands in relief. The rim has been pierced by two drill holes to facilitate suspension. Fractures to the rim have been completed repaired. At first, the plate was identified with the ‘Bologna Painter,’ who was a member of the workshop of the ‘Penthesilea Painter.’ Today, the plate is thought to be the work of the ‘Amphitrite Painter,’ formerly known as the ‘Amymone Painter.’ Women played important and wide-ranging roles in Greek religion and cultic rites. Their participation included sacrifices to honour or propitiate the gods, and rituals to bless, promote, purify, and protect the state and family. Libations of wine were common. Other offerings could include flowers, fruit and grains, meat and blood sacrifices (usually of animals), as well as tokens and votive offerings. This plate was purchased by the UNE Museum of Antiquities in 2005 to commemorate Mrs Irene McCready (1926-2003), a long-time benefactor of the Museum. The purchase also served to mark the 50th Anniversary (2004) of the grant of autonomy to the New England University College (formerly a college of the University of Sydney 1938-1954), which established the University of New England. Gifts for the purchase were provided by Leo Chan, Carrie Conolly, Audrey Edgar, Louise Hayworth, GHR Horsley, Kwan & Pansy Lam, Rosemary Leitch, Kyriakos Michaelides, Mavis Slack, and Graham & Helen Wilson, the A.G. & IC. McCready Fund, and Leon & Anna Preibish Fund. Credits: Dr Bronwyn Hopwood, July 2022. References: Beazley, J.D., Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters, Oxford 1963. Charles Ede Catalogue of Athenian Pottery, item 15, London 2004. Dillon, M.P., Eidinow, E., & Maurizio, L., eds., Women and their Ritual Competence in the Greco-Roman Mediterranean, Routledge, Abingdon 2017. Dillon, M.P., Girls and Women in Classical Greek Religion, Routledge, London 2002. Moore, M.B., ‘Attic red-figured and White-ground Pottery,’ The Athenian Agora, 30 (1997) iii-ix+xi-xvii, 1-3, 5-77, 79-357, 401-419, Type A: 1187-1195 and pl.113: 1196 (P2786). Jain Shrine MA1997.21.1 Collection: Asia. Dimensions: height 128mm, width 87mm. Northern India. 18th-19th century BC. Cast Brass-Copper Alloy. This small shrine shows a central figure seated cross-legged on a throne, set upon a raised dias, beneath an ornate, perforated canopy, and surrounded by smaller figures. The eyes, forehead diadem (or third-eye), and chest ornament of the central figure have been inlaid with silver, and a votive inscription has been incised on the reverse of the shrine. Made from cast metal, in 1997 it was incorrectly identified as an early 20th century Buddhist shrine showing the goddess Tara. In 2017 it was reidentified by Peter Lane Galleries as a Jain Shrine of the 19th century or earlier. In 2018 it was the subject of a Significance Assessment conducted by Stephen O’Shea, which found the shrine to be characteristic of those produced in North-Western India in the 18th Century. Further work on the poorly preserved inscription is required before the date of the shrine can be determined with any certainty. Jainism was founded in its current form in the 6th century BC by Vardhamana Mahavira, but its origins can be traced back to the impact of the Sramana Movement in Palanpur, Western India. It is an ascetic religion emphasising ethical conduct and personal purity. Jains hold that the soul is subject to rebirth until it rids itself of Karma, thereby achieving liberation. Jainism is focused around teachers called Tirthankaras who, having attained enlightenment, share their knowledge with their disciples. Twenty-four Tirthankaras are acknowledged, the last of whom was Mahavira. The monastic order formed by Jain disciples is considered to be India’s oldest continuous monastic tradition. Jain shrines are memorials set up to honour Tirthankaras. One of the most famous shrines found at Kankali Tila, Mathusa, contains Jain artefacts from the 2nd century BC to the 12th century AD. As the Jain population has become more mobile, portable shrines like this one have become more prevalent. Common iconographic features of Jain shrines include the depiction of the Tirthankara seated in the dhyonasana or contemplation and meditation pose; the throne of the Tirthankara upheld by an animal or symbol particularly associated with the Tirthankara depicted; a Srivatsa mark appearing on the chest of the Tirthankara after the 1st century AD; and two pairs of mythical female and male figures, known as Yaksini and Yakshas, depicted on either side of the Tirthankara. The ornate canopy suspended above the Tirthankara is usually held in place by two elephants, and topped by a tiered, conical, parisol. The ovoid shapes arranged in three groups of three in front of the Tirthankara on UNEMA’s Jain shrine have been identified, controversially, as unbroken grains of rice representing the eight ashtamangola or auspicious signs of Jainism. There are, however, nine ovoids. Several similar shrines held in other museums also have nine ovoids, but these are usually arranged from left to right in two groups of five and four. While the group of five could refer to the five Mahavratas or great vows of Jainism, and the group of four to the four Kashaya or passions of Jainism, the arrangement of these ovoids on UNEMA’s shrine in three groups of three suggests these might in fact refer to the Nav Tattvas or nine fundamental principles of Jainism. The lions on the legs of the Tirthankara’s throne may indicate that the central figure is Mahavira himself, whose symbol was the lion, however lions frequently appear on the throne legs of other Tirthankaras. The symbol of the Tirthankara depicted usually appears in the square plague centred beneath the seat of the throne. No such symbol can be easily discerned on the UNEMA shrine. The lowest of all the figures found at the very centre front of the shrine is said to represent a devotee. The circular line surrounding this devotee is thought to indicate that the devotee has yet to attain liberation, and that they still live bound within their own world. Credits: Dr Bronwyn Hopwood & Stephen O’Shea, June 2022. References: Balcerowicz, P., Early Asceticism in India: Ajivikism and Jainism, Routledge, New York 2016. Bernard, E., “Transformations of Wen Cheng Kongjo: The Tang Princess, Tibetan Queen and Buddhist Goddess Tara,” in Moon, B., & Bernard, E., eds., Goddesses who Rules, OUP, Oxford 2000, 149-164. Beyer, S., The Cult of Tara: Magic and Ritual in Tibet, University of California Press, Berkeley 1973. Bruhn, K., “The Grammar of Jina Iconography I,” Berliner Indologische Studien 8 (1995) 229-283. Bruhn, K., ‘The Grammar of Jina Iconography II’, Berliner Indologische Studien. 13-14 (2000) 273- 337. Caillat, C., “Jainism” in Kitagawa, J., The Religious Traditions of Asia, Routledge, Abington 2002, 97-109. Cort, J., Jains in the World: Religious Values and Ideology in India, OUP, Oxford 2001. Dundas, P., The Jains, Routledge, London 2002. Finegan, J., An Archaeological History of Religions of Indian Asia, Paragon House, London 1989. Flugel, P., Studies in Jaina History and Culture: Disputes and Dialogues, Routledge, London 2006. Fohr, S., Jainism: A Guide for the Perplexed, Bloomsbury Publishing, London 2015. Crab Claw and Bandicoot Jaw Necklace MA1988.16.1 Collection: Oceania. Dimensions: circumference 720mm. Lumi, East Sepik Province, Papua New Guinea. c.1972-1974. Bone, shell, crab legs, plant stems, and string. This ornament was collected by an Australian Government Patrol Officer, known as a kiap, in the vicinity of Lumi, East Sepik, Papua New Guinea. This region is home to the Wapi peoples. The ornament was collected sometime between 1972 and 1974, just before Papua New Guinea was established as a fully sovereign state in 1975. The ornament has been created from bone and plant material threaded together, in alternating straight segments and decorative clusters, to form a necklace-like structure. Following an inspection of eight-hundred-and-thirty-six New Guinean necklaces, it was observed that traditional New Guinean necklaces seem to be created using material from between one and three different animal species. UNEMA’s necklace is highly unusual because it has been created using nine different animal species. Present on the ornament are the lower jawbones of two different bandicoot-like creatures, the long-nosed echymipera and Clara’s echymipera, the lower jawbones of the common spotted cuscus and the lowland ringtail possum, the lower jawbone of an unidentified lizard-like reptile, and the lower jawbone of a snake, possibly the smooth-scaled death adder. The straight spacing lengths between the eleven jawbone clusters are made from crab legs and the stems of an unknown plant. A twelfth cluster on the necklace is composed of common egg cowrie shells and a ring of human bone, most likely taken from the femur of the upper leg or tibia of the lower leg. Set slightly off-centre on the necklace, this cluster creates a unique pendant. When you look closely at the various jawbones, you can see that these have been partially charred. This charring is uneven, with the outer extremities left largely untouched. The reason for this uneven charring is unclear. Although charring can be observed on other New Guinean jawbone necklaces, it tends to be much darker, more uniform, and affects the entire jawbone. The unusual length of this ornament has led one Sepik anthropologist to hypothesise that UNEMA’s ornament is not a necklace, but a ceremonial girdle designed to ‘clack’ against a phallocrypt (a sheath made from a gourd, worn over the penis), during a sickness-curing dance. Given the lack of examples of other clacking girdles made from jawbones that use ornamental clusters in their designs, and given the relative fragility of the jawbones, this suggestion does not seem convincing. Regardless of whether it is a clacking girdle or an exceptionally long necklace, the use of unique ornamental jawbone clusters, a human bone pendant, and an unusually high number of animal species ensures that this ornament remains mysterious. Credits: Andrew Hamilton & Bronwyn Hopwood, May 2022. References: Craig, B., Senior Curator of Foreign Ethnology, South Australian Museum, Personal Communication 17th January 2020. Flannery T.F. & Seri, L., “The mammals of Southern West Sepik Province, Papua New Guinea: their distribution, abundance, human use and zoogeography,” Records of the Australian Museum 42.2 (1990) 173–208. Friede, J.H., Terence, E., & Hellmich, C., eds., New Guinea Highlands: art from the Jolika Collection, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, San Francisco 2017. Holthuis, L.B., “Notes on Indo-West Pacific Crustacea Decapoda I and I,” Crustaceana 42.1 (1982) 26–36. Holthuis, L.B., “Notes on the localities, habitats, biology, colour and vernacular names of New Guinea freshwater crabs (crustacea Decapoda, Sundathelphusidae),” Zoologische Verhandelingen 137 (1974) 1–47. Hopwood, B., “UNE Museum of Antiquities,” in Ridley, R., with Marshall, B. & Morrell, K., eds., Fifty Treasures: Classical Antiquities in Australian and New Zealand Universities, ASCS, Melbourne 2016, pp.64-65. Menzies, J.I. & Pernetta, J.C., “A taxonomic revision of cuscuses allied to Phalanger orientalis (Marsupialia: Phalangeridae),” Journal of Zoology 1.3 (1986) 551–618. Tate, G.H.H., “Results of the Archbold Expeditions. No. 60: Studies in the Peramelidae (Marsupialia),” Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 92.6 (1948) 313–346. van Deusen, H.M. & Kent, K., “Range and habitat of the bandicoot, Echymipera clara, in New Guinea,” Journal of Mammalogy 47.4 (1966) 721–723. Warburton, N.M. & Travouillon, K.J., “The biology and palaeontology of the Peramelemorphia: a review of current knowledge and future research directions,” Australian Journal of Zoology 64.3 (2016) 151–181. Watters, P., “A necklace made from crab legs and the jaw bones of bandicoots, possums, and reptiles,” PastPerfect, University of New England, Armidale 1988, MA1988.6.1. Williams, D., “Snakes of Papua New Guinea,” in Williams, D.J., Jensen, S.D. & Winkel, K.D., eds., Clinical Management of Snakebite in Papua New Guinea, Independent Publishing Pty. Ltd., Port Moresby 2004, 1–23. Wilson, N., ed., Plumes and pearlshells: art of the New Guinea Highlands, Art Gallery of NSW, Sydney 2014, 295–348. Black-Glaze Italic Boar MA1965.2.1 Collection: Italia. Dimensions: height 11cm, width 7.65cm, length 19.07cm. Apulia. Southern Italy. 4th century BC. Terracotta. This charming zoomorphic vessel is a well-preserved example of Italic black-glaze ‘plastic’ pottery. It is an askos fashioned in the shape of a boar, sitting on its haunches with snout raised. The vessel’s narrow neck with pronounced deverted rim stands upright from the neck of the boar, behind which a long handle rises over and along the back of the boar. From the end of the handle the rump curves down to the tail, which is curled flat. The face of the boar forms the spout of the vessel. The eyes, mouth, and snout are carved in high relief, with the nostrils, whiskers, eyelids, and eyebrows left free of black glaze. The molded ears, which protrude sideways and forward from the head, have been damaged, exposing the pottery beneath. Lines have been etched and then overpainted in white along the spine of the boar in an even herring-bone pattern, to represent rough tufts of hair. Minute traces of a broad white stripe encircling the girth are also present. When tipped, liquid would have poured from a small hole in the boar’s tightly pursed mouth. Askoi are closed, vase-shaped, pottery vessels with a filling spout and handle, thought to have been used as pouring and drinking vessels on social and ceremonial occasions. Zoomorphic askoi have been recovered, mainly from funerary contexts, on the Italic Peninsula and around the Mediterranean basin from the 3rd millennium BC. Originally misidentified by Hesperia Art as an ‘Etruscan boar dating to 450-300 BC,’ it is likely that MA1965.2.1 is of Apulian manufacture from the 4th century BC. Both wild boar and domesticated pigs were known on the Italic Peninsula in the 4th century BC, and wild boar hunts were a particularly popular past-time. UNEMA’s records indicate that in 1965 the askos was missing both forelegs. Although no documents provide an account of the restoration of the legs, it is readily apparent that replacement forelegs were fashioned to help balance the vessel for display. Curiously, the photographic record suggests that the forelegs were originally fashioned in a straight, upright pose, typical of other boar-shaped askoi. At some point, however, the forelegs were remodelled, being tucked backwards beneath the boar to portray it as kneeling. Future conservation work on the boar, in line with best practice, will require the tucked-under forelegs to be replaced with straight forelegs composed of a material that can be readily differentiated from the original body of the vessel. World-wide, there are only twenty-two known examples of crouching wild boar askoi. UNEMA’s Italic Boar is the only example found in Australia. Affectionately known as ‘M. Porcius Cato’ (Mr. Pig the Wise), this boar is the unofficial mascot of the UNE Museum of Antiquities (UNEMA). Credits: Dr Bronwyn Hopwood & Dianne Eyre, April 2022. References: De Puma, R.D., ‘Black-Glazed Boar Askos’, in Animals in Ancient Art from the Leo Mildenberg Collection, A. P. Kozloff (ed.), Cleveland, The Cleveland Museum of Art in cooperation with Indiana University Press, 1981, pp. 165-6. De Puma, R.D., Etruscan Art in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York 2013. Eyre, D., Significance2.0 and MA1965.2.1: The so-called Etruscan black-glazed ‘plastic’ pottery boar 450-300 B.C.,” Museum of Antiquities, University of New England 2020. Glanzman, W.D. ‘Etruscan and South Italian Bird-Askoi: A Technological View’ in Expedition: The Magazine of the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, vol. 29 no. 1, 1987, pp. 40-48. Hesperia Art Bulletin XVII, item no.112. Hopwood, B., “UNE Museum of Antiquities,” in Ridley, R., with Marshall, B., & Morrell, K., eds., Fifty Treasures: Classical Antiquities in Australian and New Zealand Universities, ASCS, Melbourne 2016, pp.68-69. Lega, C., Fulgione, D., Genovese, A., Rook, L., Masseti, M., Meiri, M., Cinzia Marra, A., Carotenuto, F. and Raia, P. ‘Like a pig out of water: seaborne spread of domestic pigs in Southern Italy and Sardinia during the Bronze and Iron Ages’ in Heredity, vol. 118, 2017, pp. 154-159. Lombardo, M. ‘Iapygians: The Indigenous Populations of Ancient Apulia in the Fifth and Fourth Centuries B.C.E.’ in The Italic People of Ancient Apulia: New Evidence from Pottery for Workshops, Markets, and Customs, Cambridge, 2014, pp. 36-68. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York Terracotta askos in the form of a boar 4th century B.C., https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/254213, accessed 14 January 2020. The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston Unknown Greek Askos in the shape of a Boar, https://emuseum.mfah.org/objects/72913/askos-in-the-shape-of-a-boar?ctx=589d91eb29a01a25d40716abe13f00ee5e7f1f24&idx=0, accessed 18 March 2020. Perkins, P., Etruscan Bucchero in the British Museum, London 2007. Riccardi, A. ‘Apulian and Lucanian Pottery from Coastal Peucetian Contexts’ in The Italic People of Ancient Apulia: New Evidence from Pottery for Workshops, Markets, and Customs, T.H. Carpenter, K.M. Lynch and E.G.D. Robinson (eds), Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2014, pp. 133-151. RISD Museum, Rhode Island, U.S. Italo-Greek, Apulia, Oil Container (Askos) in the Form of a Boar, late 300s BCE-early 200s BCE, https://risdmuseum.org/art-design/collection/oil-container-askos-form-boar-199698, accessed 18 April 2020. Sublimi Saponetti, S. ‘I resti animali di Gravetta (Lavello PZ)’ in Comunità indigene e problem della romanizzazione nell’Italia centro-meridionale (IVº-IIIº Sec, Av. C.), J. Mertens and R. Lambrechts (eds), Brussels, Actes du Colloque International, 1991, pp. 105-8. Yntema, D. The Archaeology of South-East Italy in the first millennium BC: Greek and Native Societies of Apulia and Lucania between the 10th and the 1st century BC, Amsterdam, Amsterdam University Press, 2013. Yntema, D. ‘The Pre-Roman Peoples of Apulia (1000-100 BC)’ in The Peoples of Ancient Italy, Gary D. Farney and Guy Bradley (eds), e-book, De Gruyter, Inc., DOI 10.1515/9781614513001-018, accessed 14 April 2020. Roman Surgical Instruments MA1974.2.1-6 Collection: Rome. Dimensions: height 138-154mm. Italy. 2nd century AD. Bronze. This medical kit is a set of six surgical tools from ancient Italy. Most surgical instruments surviving from Roman antiquity are made of bronze, because this metal alloy is more resistant to rust than iron or steel. UNEMA’s surgical kit includes a spatula, a scoop with an elongated bowl, a hook, a scoop with a small round bowl (slightly damaged where it has been pushed in on one side), a curved scraper or scalpel, and a two-pronged fork. All six implements have ends terminating in probes. In form, these tools are highly sophisticated and practical, and vary little from modern medical implements. Hippocrates of Kos (460-370 BC), sometimes referred to as the father of medicine, is said to have argued that “All instruments ought to be well suited for the purpose in hand as regards their size, weight, and delicacy” (1.58). The weight and thickness of UNEMA’s tools is largely consistent with the strength required by their purpose, but they also include simple yet elegant decorations. Each of these six tools are adorned with three, evenly spaced, incised bands of double lines, now very faint, starting at the neck of each instrument. Of these tools, the hook could be used to manipulate bones, the spatula to spread medicaments or depress the tongue, the scalpel to cut or scrape skin and viscera, the scoops to extract superfluous matter during exploration or, when heated, to cauterise wounds, and the forked prong to extract embedded weaponry or to pierce and remove matter such as tonsils. Although some anaesthetics were known in Roman times, they do not appear to have been widely used, and several ancient medical treatises refer to the cries of patients during treatment. Moreover, the lack of antiseptics and a general understanding of sterilisation made many medical procedures dangerous. Credits: Dr Bronwyn Hopwood, March 2022. References: Bliquez, L.J., “Greek and Roman Medicine,” Archaeology 34.2 (1981) 10-17. Charles Ede Catalogue 95, item 10 (London 1974). Ede, C., Collecting Antiquities: An Introductory Guide, UK 1975. Hopwood, B., “UNE Museum of Antiquities,” in Ridley, R., with Marshall, B., & Morrell, K., eds., Fifty Treasures: Classical Antiquities in Australian and New Zealand Universities, ASCS, Melbourne 2016, pp.64-65. Jackson, R., Medicine and Healing in the Ancient Mediterranean, Oxbow Books, London 2014. Kirkup, The Evolution of Surgical Instruments: an illustrated history from ancient times to the Twentieth Century, Novato, California 2006. Milne, J.S., Surgical Instruments in Greek and Roman Times, Oxford 1907. Cypro-Archaic Bichrome IV Ware Tortoise-Shaped Vessel MA1978.106.1 Collection: Cyprus. Dimensions: height 930mm, diameter 80mm, rim 38mm. Cyprus. 750-600 BC. Buff Clay. This baby feeder is a sturdy example of Bichrome IV Ware of Cypro-Archaic origin (750-600 BC). The globular body of the feeder is tilted back on its three, triangular, stump legs, and its nipple-shaped spout is counter-balanced by a curved handle attached to the everted rim of the vessel’s short, concave-sided neck. Damage visible on the body of the feeder has been mended. The feeder is made of buff-coloured clay with a cream-buff slip, and has been decorated with black and faded red paint lines. A single black line circles the girth of the feeder on which two triangles rest, one composed of six concentric black-lines, the other of seven. The triangles are placed on either side of the feeder, between the handle and spout, like wings. A solid, black, semi-circle appears on both sides of each triangle just short of their apex. Two parallel black lines encircle the neck of the spout, and one encircles the neck of the feeder. A single red line circles the neck of the feeder above the black line, and five horizontal red lines appear down the handle. The end of the spout, and three of the eight diamond segments in the central lattice of both triangles are painted red. There is a red dot at the apex of all but the outermost triangle. Two, slightly curved, vertical lines of red dots are traced on either side of the triangles. Finally, two small circles, each with an off-centred dot inside them, and a fine black line above them, are found between the red nose and central swelling of the feeder’s spout. The effect of this decoration is deliberately zoomorphic, and designed to depict the drinking vessel as a bird, ̶ possibly a duck. The choice of a duck is highly appropriate given that the Greek term τό νηττάριον, meaning “duckling,” was used in antiquity as a term of endearment. Another ‘plastic’ or zoomorphic form used for baby feeders was that of a mule carrying amphorae. Plain and undecorated feeders, like the one held in UNEMA’s Woite Collection, are also well known. Many baby feeders have survived from antiquity. Some have been found with glazed pebbles inside them. When these vessels were tipped for drinking, the pebble inside would have moderated the flow of milk from the feeder’s spout. And, once the milk had been drunk, the pebble would have acted as a rattle. The baby feeder featured here belongs to UNEMA’s Stewart Collection. James Stewart was the first Professor of Near Eastern Archaeology at the University of Sydney, an Honorary Curator of Sydney’s Nicholson Museum, and the first Australian archaeologist to lead an international dig. His pioneering work on ancient Cypriot ceramics remains an important archaeological touchstone. UNEMA is home to Stewart’s private collection of Cypriot material, which spans the Stone, Bronze, Iron, and Byzantine eras. Credits: Dr Bronwyn Hopwood, February 2022. References: Aristophanes Plutus 1010-1011, in Rogers, B.B., ed., Aristophanes, with the English translation of Benjamin Bickley Rogers, Heinemann, London 1924. Hopwood, B., “UNE Museum of Antiquities,” in Ridley, R., with Marshall, B., & Morrell, K., eds., Fifty Treasures: Classical Antiquitiesin Australian and New Zealand Universities, ASCS, Melbourne 2016, pp.64-65. Myres, J.L., Handbook of the Cesnola Collection of Antiquities from Cyprus, New York 1914. Noble, J.V., ‘An Unusual Attic Baby Feeder,’ AJA 76.4 (1972) 437-438, plate 95. Powell, J., Love's Obsession: The Lives and Archaeology of Jim and Eve Stewart, Kent Town SA 2013. Vickers, M., ‘Museum Supplement: Recent Acquisitions of the Greek and Etruscan Antiquities by the Ashmoleon Museum, Oxford 1981-90’, JHS 112 (1992) 246-248, plates VII-VIII. Webb, J.M., Cypriote Antiquities in Australian Collections I, Jonsered 1997. Bust of Serapis MA2017.2.1 Collection: Egypt. Dimensions: height 140 mm. Alexandria. Egypt. 1st-2nd centuries AD. Calcite Alabaster. Portrait busts are sculptural works that depict a person from the chest up. Both heads and busts could be inserted into free standing sculptures and relief carvings, as well as displayed on their own. In antiquity portrait busts were used to depict real people, legendary characters, and divinities. Portrait busts appeared in both public and private settings, including temples, altars, civic buildings and spaces, in festive, triumphal, and funerary processions, as well as in homes and tombs. Statues and portrait busts were frequently painted, gilded, dressed, and adorned. This bust depicts the deity Serapis (Sarapis) in classical form with five distinct locks of hair on the forehead and a full beard, which is parted symmetrically into two halves. An indentation on the top of the head marks the place where a crown was once fixed. This would have been a basket-shaped crown (kalathos or modius), possibly decorated in relief with vines or floral motifs. Made of calcite alabaster, the bust has been dated to the early Roman period (1st-2nd centuries BC) based on comparisons of style. Busts of this type have been identified by many scholars as copies of an original cult statue created by the famous Greek sculptor Bryaxis for the Serapeum of Alexandria in the 3rd century BC. While the attribution of the cult statue to Bryaxis is unsubstantiated, this portrait bust was likely modelled after one or more of the cult statues found in that Serapeum. Many copies of this bust type were made in antiquity, and examples have been found in glass, metal, stone, and terracotta. Close parallels of the UNEMA bust can be found in the Graeco-Roman Museum in Alexandria (22158) and in the National Gallery of Victoria (4103-D3), although these vary in size and quality. The deity Serapis appears to have been created by Ptolemy I Soter, since the name Serapis is not attested prior to Soter’s reign. The name ‘Serapis’ is derived from that of the Egyptian god Osiris-Apis (thus Ser-Apis). In bilingual texts from the Ptolemaic Period he was associated with kingship, fertility, and the afterlife, as well as with solar, healing, and fertility attributes through his association with the gods Zeus, Asklepios, Helios, Hades and Dionysos. Although his name is Egyptian, Serapis’ image was entirely Greek. He is commonly depicted seated on a throne, with one hand raised holding a staff or sceptre and the other hand resting on Cerberus, the three-headed dog guarding Hades. The main cult centre of Serapis was the Serapeum (Serapeion) in Alexandria, but the popularity of the divine couple Serapis-Isis, saw shrines to their cult spread throughout the Roman Empire, as far away as Roman Britain. UNEMA’s Serapis bust was purchased in Alexandria in the early 20th century by Gustave Mustaki, a prolific collector of anitquities, and exported to London in 1949. Passing by descent to Mustaki’s daughter, it was purchased by Charles Ede Ltd of London. With the assistance of Kwun & Pansy Lam, it was acquired by UNEMA to celebrate the centennary of the birth of UNE Classicist and UNEMA Sponsor, Mr Alfred Glenn (Mac) McCready (1916-1996). Credits: Dr Bronwyn Hopwood & Dr James Gill, January 2022. References: Bricault, L., & Versluys, M.J., Meyboom, P.G.P., eds., Nile into Tiber: Egypt in the Roman World, Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference of Isis Studies, May 11–14 2005, Faculty of Archaeology, Leiden University, Brill, Leiden 2007. Bricault, L., & Versluys, M.J., eds., Power, Politics and the Cults of Isis: Proceedings of the Vth International Conference of Isis Studies, Boulogne-sur-Mer, October 13–15, 2011, Brill, Leiden 2014. Fejfer, J., Roman Portraits In Context, De Gruyter, Berlin 2008. Flower, H.I., Ancestor Masks and Aristocratic Power In Roman Culture, Clarendon Press, Oxford 1996. Kleiner, D.E.E., Roman Sculpture, Yale University Press, New Haven 1992. Kousser, R.M., Hellenistic and Roman Ideal Sculpture: The Allure of the Classical, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2008. Pfeiffer, S., "The God Serapis, his Cult and the Beginnings of the Ruler Cult in Ptolemaic Egypt," in McKechnie, P., & Guillaume, P., eds., Ptolemy II Philadelphus and his World, Brill, Leiden 2008, x-x. Renberg, G.H., Where Dreams May Come: Incubation Sanctuaries in the Greco-Roman World, Brill, Leiden 2017. Smith, M., Following Osiris: Perspectives on the Osirian Afterlife from Four Millennia, Oxford University Press, Oxford 2017. Sobocinski, M., Grunow, E., Friedland, E.A., & Gazda, E.K., eds., The Oxford Handbook of Roman Sculpture, Oxford University Press, New York 2015. Stewart, P., Statues in Roman Society: Representation and Response, Oxford University Press, Oxford 2003. Takács, S.A., Isis and Sarapis in the Roman World, E. J. Brill, Leiden 1995. Thompson, D.J., Memphis Under the Ptolemies, 2nd edn., Princeton University Press, New Jersey 2012. Meet UNEMA’s Pilgrim Flask with Gladiators MA1977.1.1 Collections: Roman. Dimensions: height 171 mm. Eastern Roman Empire. Greece. 3rd-4th centuries AD. Biscuit-coloured earthernware. A Pilgrim Flask is a stamped pottery ampulla or terracotta flask used for religious or ritual purposes. It’s characteristic canteen-like shape has a round narrow body and short neck, with either two handle loops or two to four axial belt tabs. A chord or chain was passed through the loops or tabs to secure the bottle’s stopper and to assist with carrying. These vessels have a very long history that can be traced from the civilisations of Mesopotamia and Egypt, to the Greco-Roman and Byzantine world, and regions of the Indus and Asia. Pilgrim flasks came to be made from pottery, leather, worked metal, and even glass, and are known from the 12th century BC through to the 17th century AD. This utilitarian flask was ideal for taking liquids (water or wine) on journeys, for holding oil and libations to be used at religious sanctuaries, and later as souvenirs or reliquary-holders to be brought home from pilgrimages. The flask could serve as a protective talisman for pilgrims on sojourn, while later sumptuous versions appear to have been made purely for ornamental purposes and the display of status. Pottery flasks like the one in UNEMA were usually made from two separately moulded disks, which were then joined together, before the neck and handles were added. The moulds used to create the discs could be carved to create decorative reliefs on the surface of the flask. These reliefs could depict simple decorative patterns or complicated references to mythological, literary, and religious figures, or to popular scenes from daily life. The UNEMA pilgrim flask depicts gladiatorial combat. The figure of a retiarus advancing with his trident, ready to fight, is shown on both sides of the flask, although one side is much more worn than the other. Decorated with palmettes and rounds, the flask bears the retrograde Greek inscription “AKAKIOU,” and the whole composition is surrounded by a frieze of animals. Akakias is a personal name attested for the 3rd and 4th centuries AD, and the flask may have commemorated a popular gladiator of the day. The flask, which has been dated using thermoluminiscence, was purchased by UNEMA in 1976 from Charles Ede Ltd of London and accessioned into the collection in 1977. Credits: Dr Bronwyn Hopwood, December 2021. References: Anderson, W., 'An Archaeology of Late Antique Pilgrim Flasks,' Anatolian Studies 54 (2004) 79-93. Burn, L., Higgins, R., Walters, H.B., & Bailey, D.M., Catalogue of Terracottas in the British Museum, BMP, London 1903-2001. Cameron, A., 'Images of authority: elites and icons in late sixth century Byzantium,' Past and Present 84 (1979) 3-35. Campbell, S., 'Armchair pilgrims: ampullae from Aphrodisias in Caria,' Medieval Studies 50 (1988) 539-545. Dalton, O.M., Catalogue of Early Christian Antiquities and Objects from the Christian East in the Department of British and Medieval Antiquities and Ethnography of the British Museum, London 1901. Davis, S.J., 'Pilgrimage and the cult of Saint Thecla in late antique Egypt,' in D. Frankfurter, ed., Pilgrimage and Holy Space in Late Antique Egypt, Leiden 2001, 303-339. Charles Ede Ltd., Catalogue 105, No.39. Griffing Jr., R.P., 'An early Christian ivory plaque in Cyprus and notes on the Asiatic ampullae,' Art Bulletin 20 (1938) 266-279. Hahn, C., 'Loca sancta souvenirs: sealing the pilgrim's experience,' in R. Ousterhout ed., The Blessings of Pilgrimage, Urbana, Chicago 1990, 85-96. Hayes, J.W., 'A new type of early Christian ampulla,' Annual of the British School at Athens 66 (1971) 243-248. Maeir, A.M. & Strauss, Y., 'A pilgrim flask of Anatolian origin from late Byzantine / early Ummayyad Jerusalem,' Anatolian Studies 45 (1995) 237-241. Metzger, C., Les ampoules a eulogie du musee du Louvre, Paris 1981. Thompson, F.H., 'Pilgrim flask from Meols,' Journal of the Chester Archaeological Society 43 (1956) 48-49. Meet UNEMA’s Greek Theatre Masks MA2015.7.1 & MA2015.8.1. Collections: Diorama, Greece. Dimensions: c.10 x 7 x 1 cms. Greece. Replicas 1997. Terracotta. Dramatic masks played an important role in Ancient Greek theatre. Since most plays only permitted three actors to appear on stage at a time, masks allowed each actor to play several characters, and to switch rapidly between characters during a performance. If an actor had to change masks while on stage, he would turn his back to the audience to prevent his face and the change of mask from being seen. As all actors were men, dramatic masks also helped the actors to portray female characters. The exaggerated expressions on each mask – smiling or leering for comedic masks and sad or pained for tragic masks – also helped the audience to identify characters more readily, and because the masks were larger than life they were more easily seen from seats more distant from the stage. In addition to the main characters, ancient Greek plays also had a chorus. The role of the chorus was to comment on the unfolding story, point out the moral of the play, and to speak to the main characters and audience directly. The chorus usually delivered their lines as sung narrative, often accompanied by music. A key feature of the chorus was that its members moved and spoke as a single unit. Like the main characters, the members of the chorus also wore masks, but to increase their homogeneity and unity the members of the chorus all wore the same mask. Unfortunately, no original Greek stage masks have survived as they were made from lightweight, perishable materials like cork, hair, leather, linen, and wood. Numerous depictions of these masks, however, are found in mosaics and on Greek vases, as well as in the form of terracotta dedications made to temples. For example, some of the earliest known depictions of Medusa and the Gorgons are terracotta votive masks dedicated at a shrine of Artemis in the 7th century BC (Napier 1986). In addition to masks and costumes, Greek theatre also made use of simple machines and automata. Two common mechanisms were the Ekkyklema, a large wheeled platform used to wheel onto the stage scenes which had taken place off-stage, such as the results of violence; and the Mechane, a crane-like device used to lift actors into the air, so that they could appear suddenly from behind scenery or suspended in air, especially when performing the role of a god or godddess. The terracotta Greek theatre masks displayed here were made in 1997 by Canberra ceramicist Joy McDonald. They were cast from an original for the Classics Department at the Australian National University. Note the votive tablet’s wide open mouth, entirely circular eyes, and exaggeratedly raised eyebrows. The expression is that of a pained tragic mask. Note also the representation of hair on this tablet, which in the theatre would have been provided for by use of a wig. Credits: Dr Bronwyn Hopwood, November 2021. References: Brooke, I., Costume in Greek Classical Drama, Methuen, London 1962. Bosher, K.G., Greek Theater in Ancient Sicily, CUP, Cambridge 2021. Easterling, P.E., ed., The Cambridge Companion to Greek tragedy, CUP, Cambridge 1997. Easterling, P.E., & Hall, E., eds., Greek and Roman Actors: aspect sof an ancient profession, CUP, Cambridge 2002. Foley, H., Female Acts in Greek Tragedy, Princeton University Press, Princeton 2001. Freund, P., The Birth of Theatre, Peter Owen Inc., London 2003. Kontomichos, F.,Papadakos, C., Georganti, E., Vovolis, T., Mourjopoulos, J.N.,, “The sound effect of ancient Greek theatrical masks,” Proceedings ICMC|SMC 14-20 September 2014, 1444-1452. Ley, G., A Short Introduction to the Ancient Greek Theatre, University of Chicago, Chicago 2006. McDonald, M., & Walton, J.M., ed., The Cambridge Companion to Greek and Roman Theatre, CUP, New York 2007. Pathmanathan, R.S., "Death in Greek Tragedy," Greece & Rome 12.1 (1965) 1-14. Rabinowitz, N.S., Greek Tragedy, Blackwell, Massachussetts 2008. Varakis, A., “Research on the Ancient Mask,” Didaskalia 6.1 (2004), Didaskalia.net accessed 25.10.2021 Vervain, C., & Wiles, D., “The Masks of Greek Tragedy as Point of Departure for Modern Performance,” New Theatre Quarterly 67 (2004) 254-272. Vovolis, T., & Zamboulakis, G., “The acoustical mask of Greek tragedy,” Didaskalia 7.1 (2007), Didaskalia.net accessed 25.10.2021 Wiles, D., Greek Theatre Performance: An Introduction, CUP, Cambridge 2000 Wiles, D., The Masks of Menander: Sign and Meaning in Greek and Roman Performance, CUP, Cambridge 1991. Wiles, D., Mask and Performance in Greek Tragedy: from ancient festival to modern experimentation, CUP, Cambridge 1997. Zimmerman, B., Greek Tragedy: An Introduction, trans. T. Marier, Baltimore 1991. The Temple of Inscriptions and Tomb of Pacal MA1994.10.1. Collections: Diorama, Americas. Dimensions: 45 x 18 x 37cm. Mayan Empire. Palenque, Mexico. AD 600-700. Ceramic and Craftwood. The Maya city-state of Palenque, also known as Lakamha in antiquity, flourished in Chiapas, Mexico between the 3rd century BC and 7th century AD. The formal title used by the rulers of Palenque was ajaw, which means king. In AD 615, K’inich Janaab Pakal - whose name perhaps means ‘radiant sun shield’ - became ajaw of Palenque at the age of twelve. He ruled for 68 years until his death and deification in AD 683, at the age of 88. During his reign, Pakal restored and extended the power of Palenque among the western Maya states and undertook a building program that produced some of that civilisation’s finest art and architecture. Pakal’s first construction project was a temple, which the Spanish later called El Olvidado, “The Forgotten,” on account of its distance from Lakamha. Pakal also built Palenque’s largest stepped pyramid, B’olon Yej Te’ Naah, which translated means, “The House of the Nine Sharpened Spears.” Now known as the Temple of the Inscriptions, this stepped pyramid housed Pakal’s tomb, containing his colossal stone sarcophagus, skeletal remains, and grave goods. The tomb remained undisturbed, despite numerous investigations, until 1952. Built at a right angle to the southeast of Palenque’s royal palace, the mausoleum was finished for Pakal by his son, ajaw K’inich Kan B’alam II. The Mausoleum consists of a pyramid of eight steps, on top of which a temple-like structure known as a roof comb was placed to create a ninth level. The roof comb of the Temple of the Inscriptions has been so badly damaged that only the underpinning piers remain. The dimensions of the stepped pyramid are 60m wide, by 43m deep, and 27m high. The remains of the roof comb measure 26m wide, by 11m deep, and 11m high. The largest stones, all found at the top of the pyramid, weigh between 12 to 15 tonnes. The five entrances set into the roof comb are flanked by six piers decorated with carved reliefs and hieroglyphic text. Labelled A to F, the piers were executed in brightly painted red, yellow, and blue stucco plaster, that has since deteriorated considerably. In traditional Maya stucco work, the colour red was used as a background; the colour yellow, which was associated with the underworld, was used to depict jaguar skin, and the colour blue, which was associated with the heavens, was applied to the figures of gods and to glyphic texts. Inside the roof comb, a further three monumental tablets known as the East, Central, and West Tablets, recounting 180 years of Palenque’s history, at a length of 617 glyphs provide the second-longest Maya text to have survived antiquity. The stairway passage leading down to Pakal’s crypt was set into the floor and sealed by a large stone slab and stone plugs, which helped to hide the entranceway to the crypt from both looters and archaeologists. When found and opened in 1948, it took the archaeologists four years to clear the rubble from the passageway. At the entrance to the crypt, five sacrificial victims intended to accompany Pakal into the underworld, were discovered. Inside the hut-shaped crypt, in order to sustain the weight of the pyramid above it, the chamber was strengthened by both cross-vaulting and recessed buttresses. The temple also has a duct structure that is only partially understood. The tomb itself was decorated with colourful stucco reliefs showing the transition of Pakal from mortal to divine, accompanied by figures from Maya mythology. The interpretation of the limestone lid of his sarcophagus, however, is far more controversial. Ornately and uniquely carved, the lid shows Pakal on top of the earth monster. He appears with attributes of the Maize god – tonsured hair and a turtle amulet on his chest – as he emerges from the jaws of Xibalba, the world of the dead. Above him the celestial bird and two headed serpent sit in the cross of the World Tree. This iconography shows Pakal existing between the heavens and underworld. Around the sarcophagus appear the sun, moon, stars, and other cosmological signs, as well as the named portraits of six noblemen or ancestors. A stucco portrait of the king was also found beneath the base of the sarcophagus. Inside the sarcophagus, Pakal’s skeleton was found wearing ornate jade bead necklaces, bracelets, rings, and amulets, and an impressive jade mask with eyes of obsidian, mother-of-pearl, and shell. The grave goods have been rehoused in the National Museum of Anthropology, Mexico and Pakal’s tomb in the Temple of the Inscriptions permanently resealed. The diorama displayed here was created by former UNEMA Honorary Curator Mr Pat Watters using craftwood and ceramic tile. The model uses a scale of 1/40. Credits: Dr Bronwyn Hopwood, October 2021. References: Freidel, D.A., Schele, L., & Parker, J., Maya Cosmos: Three Thousand Years on the Shaman’s Path, William Morrow and Company, New York 1993. Martin, S., & Grube, N., Chronicle of the Maya Kings and Queens: Deciphering the Dynasties of the Ancient Maya, 2nd edn., Thames & Hudson, London and New York 2008. Schele, L. & Mathews, P., The Code of the Kings: The Language of Seven Sacred Maya Temples and Tombs,Touchstone, New York 1998. Stuart, D. & Stuart, G., Palenque: Eternal City of the Maya, Thames & Hudson, London 2008. Tiesler, V., Cucina, A., & Pacheco, A.R., "Who was the Red Queen? Identity of the female Maya dignitary from the sarcophagus tomb of Temple XIII, Palenque, Mexico," HOMO 55.1 (2004) 65–76. Guenter, S., “The Tomb of K’inich Janaab Pakal: The Temple of the Inscriptions at Palenque,” Mesoweb, (undated), http://www.mesoweb.com/articles/guenter/TI.pdf, accessed 12.09.2021. Robertson, M.G., The Sculpture of Palenque, Vol.I: The Temple of Inscriptions, Princeton University Press, New Jersey 1983. Stierlin, H., The Maya: Palaces and Pyramids of the Rainforest, Taschen, London & New York 2001. Berlin, H., “The Palenque Triad,” Journal de la Société des Américanistes, n.s. 5.52 (1963) 91–99.