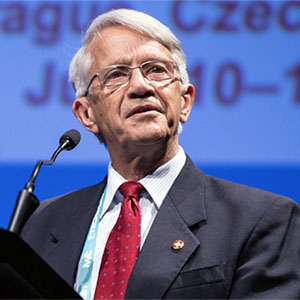

Emeritus Professor David Mellor

2021 UNE Distinguished Alumni Award Winner - Emeritus Professor David Mellor

In recognition of his ground-breaking research in Animal Welfare Science and Bioethics revolutionising the manner in which animal welfare is viewed, implemented and monitored.

Emeritus Professor David Mellor, Prague 2019

Emeritus Professor David Mellor, Prague 2019

Animal welfare pioneer

Animals – they are an integral part of our daily lives; a source of food, companionship and entertainment. It’s hard to imagine an era when our treatment of them, on farms, in zoos, in scientific laboratories and on racetracks was not as closely scrutinised as it is today. A time before the growth of the modern animal rights movements.

But when Melbourne schoolboy David Mellor enrolled in a Bachelor of Science degree at UNE in the early 1960s animal welfare didn’t yet exist. “People dealing with animals back then did the best they could,” he says. “They didn’t set out to make the lives of animals miserable, but often they were completely indifferent. They didn’t understand them as anything more than ‘dumb animals’.”

David’s studies at UNE – culminating in First Class Honours and the 1966 University Medal – convinced him otherwise. By graduation he had developed and published an original chart that drew together widely different elements of animal physiology. Subsequent students still recall its impact and, according to David, “the principle of integration the chart illustrated formed the foundation for everything to come”.

“David had left UNE before my arrival in 1968 [but the] … chart that he produced was used in our classes,” says recently retired Professor of Animal Science at the University of Queensland, Wayne Bryden. “At the time I thought ‘what an impressive achievement for a new graduate’.”

After completing his PhD in perinatal physiology at the University of Edinburgh, David worked first at the Moredun Research Institute in Scotland and then New Zealand’s Massey University, rigorously testing and expanding his theories. Informed by a growing appreciation of bioethics, he was determined to uncover what factors influenced an animal’s health and wellbeing and how they could best be enhanced. “I wanted to understand, scientifically, what vertebrates were experiencing in a range of precise circumstances,” he says.

David Mellor, Moredun Research Institute 1971

David Mellor, Moredun Research Institute 1971

David would go on to identify twin animal welfare objectives: to minimise the negative experiences animals have (like thirst and pain); and to provide them with opportunities to engage in pleasurable ones (like contentment and play). Improving the detection, treatment and prevention of pain was of fundamental importance.

The resulting Five Domains Model that David developed, which he insists is not “the gospel according to David” but the result of many collaborations, recognised that “animal welfare is very clearly about ethics in terms of our human motivations and responsibilities”. The model has been progressively updated to reflect scientific advances over time and continues to inform policies, welfare standards and codes internationally in zoos and aquaria, on racetracks, in laboratories and livestock industries.

That ability to operate at the complex interface of science and bioethics saw David establish the ground-breaking Animal Welfare Science and Bioethics Centre at Massey in 1998. Under his leadership, it soon gained a global reputation for practical, science-based and ethical advice, education and solutions to animal welfare problems. David held the chair of Applied Physiology and Bioethics in addition to Animal Welfare Science at Massey for 20 years – a period of active engagement with institutions, governments, regulators and veterinarians around the world.

“Some people say that everything we do in relation to animal welfare regulations must be based on science,” David says. “Science informs the judgements we make, but it does not tell us what those judgements should be; that’s when we bring in ethics and sociology and history and culture. These things enable us, within our context, to do the very best we can on behalf of animals.

“It also brings those with whom we disagree into the discussion. As long as they remain within the law, I have always been a strong advocate for those who are against animal use – animal rights people and anti-vivisectionists – because they hold up a mirror to another view.”

Under animal welfare principles, the use of animals for our own purposes is acceptable provided those purposes are legitimate and humane. Animal rights principles say that because animals cannot give or withhold consent to participate, any use is a form of abuse and exploitation.

“But these are complementary positions,” David says. “It’s important to recognise both, and for animal users to acknowledge the genuine concerns that others have. That said, we predominantly live in cultures and countries where animal use is acceptable, so we have an obligation to do the very best we can in all circumstances to achieve the objectives of acceptable purposes and humane treatment.”

Advocating for understanding has set David’s approach apart, at a time of rising vegetarianism and growing animal welfare scrutiny internationally. “If you have understanding, it opens the heart to seeing other peoples’ ways of viewing the world,” he says.

“That’s very important in animal welfare. Because while animal welfare has evolved, and countries that never previously thought about it are now thinking about it, there will always be areas that require attention.”

His impressive record and reputation as a scientist, scholar and communicator has earned David a string of major awards, most notably being made an Honorary Associate of the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons – a rare distinction given to few non-veterinarians – and the Universities Federation for Animal Welfare medal. But colleagues say David’s research achievements are matched by his contributions to science leadership and mentorship, his humility and inclusiveness.

“David’s work has helped to create the modern field of animal welfare science,” says Professor and NSERC Industrial Research Chair in Animal Welfare Daniel Weary, of the University of British Columbia. “He is one of the most recognised and influential minds working in this area [and] … his work has had a great impact outside of academia, influencing governmental and non-governmental policy.”

An individual of “exceptional kindness and generosity”, who infects others with his “seemingly fathomless enthusiasm,” David’s efforts “have helped countless students and colleagues, as well as animals and people who care for them”, according to Professor Weary.

Having “realigned” (not retired) in 2018, David now has a little more time to walk his beloved retired working dog Bess – “animals are an important part of our lives, even if we don’t eat them”, he says. And after years of working with everything from sheep and chickens to thoroughbred horses and pigs, in laboratories and chilly paddocks from Scotland to New Zealand, David is appreciative of all that animals have taught him about people.

“Not just about how we function as living organisms, but also how we make sense of all we believe,” he says. “Animal science has given me the rigour to travel down some really diverse avenues and to plumb the depths of meaning for different people … to respect their beliefs and the integrity that comes with those beliefs. It has made my life meaningful.”