Sexual Harm & Gender-Based Violence

If you or someone else is in immediate danger, or in an emergency situation, call the Police on 000 (triple zero).

If there is no immediate danger but you or someone else needs the police, call the 24/7 Police assistance line on 131 444.

Sexual harm and gender-based violence is unlawful, unacceptable and is not tolerated at UNE.

All members of the University community have the right to be treated with dignity and respect, and to live, work, socialise, and study in a safe environment.

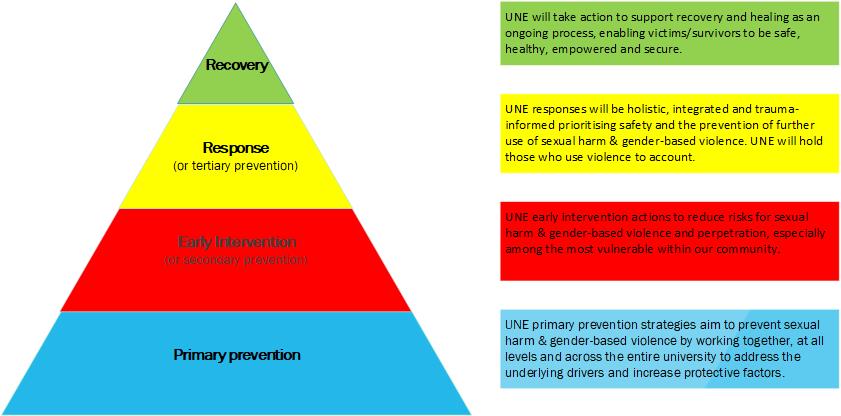

The UNE framework for the prevention and response to gender-based violence and sexual harm involves working across all levels of the university, for the entire university community, to change and transform the social context so that the drivers of the sexual harm & gender-based violence are recognised, addressed and eliminated. It moves beyond a focus on individual behaviours to consider the broader social and cultural factors that drive sexual harm and gender-based violence such as gender inequality.

The framework embodies research based and expert led primary prevention frameworks in accordance with the Primary Prevention of Sexual Harm in the University Sector - Good Practise Guide (Universities Australia), the Our Watch primary prevention approach, the NSW Sexual Violence Plan 2022-2027, and the National Higher Education Code to Prevent and Respond to Gender-based Violence.

UNE will ensure the safety, privacy and wellbeing of the people impacted by sexual harm and gender-based violence as a priority. UNE will ensure all internal processes are followed in a manner that minimises harm, so all participants in the process are supported, have clear information about the process, and how procedural fairness will be provided while ensuring confidentiality is understood and maintained.

Sexual harm is non-consensual behaviour of a sexual nature that causes a person to feel uncomfortable, frightened, distressed, intimidated, or harmed either physically or psychologically. Sexual harm includes sexual harassment and sexual assault. Sexual harm occurs when there is no freely given agreement, or when someone is being coerced or manipulated into any unwanted sexual activity, or when someone does not have the capacity to give or withdraw consent. Sexual harm can impact anyone regardless of their sex, gender identity or sexual orientation. Sexual harm does not have to be repeated or continuous; it can be a one-off incident. Examples of behaviours that constitute sexual harm include (but are not limited to): Sexual harm is not consensual sexual interaction, flirtation, attraction or friendship which is invited, mutual, or reciprocated, but it can occur if a person continues with the relevant behaviour after being put on notice that the behaviour is no longer agreed to or welcome. When someone has a sexual experience they don't want, or are forced into any kind of sexual act by another person, they’ve experienced sexual harm. Sexual harm can happen in lots of different ways: The effects of sexual harm are different for everyone. Gender-based violence is the use and abuse of an imbalance of power and control to humiliate and make a person or group of people feel inferior and/ or subordinate based on their factual or perceived sex, gender, sexual orientation, and/or gender identity. This type of violence is deeply rooted in the social and cultural structures, norms, and values that govern society and is often perpetuated by a culture of denial and silence. Gender inequality is a human construct, and we can overcome it. It is caused by gender bias in our systems, structures and attitudes, which create an environment where women, girls and people of diverse genders and sexualities are denied their rights to learn, earn equal pay and hold leadership positions. Gender-based violence can happen in both private and public. Gender-based violence can be sexual, physical, verbal, psychological (emotional), or socio-economic and it can take many forms, from verbal violence and hate speech on the Internet, to rape or murder. It can be perpetrated by anyone: a current or former spouse/partner, a family member, a colleague from work, schoolmates, friends, an unknown person, or people who act on behalf of cultural, religious, state, or intra-state institutions. Gender-based violence, as with any type of violence, is an issue involving relations of power. It is based on a feeling of superiority, and an intention to assert that superiority in the family, at school, at work, in the community or in society as a whole. LGBT+ people (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and other people who do not fit the heterosexual norm or traditional gender binary categories) also suffer from violence which is based on their factual or perceived sexual orientation, and/or gender identity. For that reason, violence against such people falls within the scope of gender-based violence. Men can also be targeted with gender-based violence however the number of such cases is significantly smaller, in comparison with women, but it should not be overlooked. Drivers of Gender-Based Violence Violence against women is preventable. To stop this violence before it starts, we need to address the social conditions that drive it. The research shows that gender inequality creates the social conditions for violence against women to occur. The Domestic Violence Resource Centre Victoria (DVRCV) has developed a series of tip sheets on the four gendered drivers. These tip sheets are great primary prevention tools that can be used to increase understanding about how men’s control of decision making and limits to women’s independence drive violence against women. The four gendered drivers: Whether you are responding to a victim or implementing prevention strategies to stop sexual harm and gender-based violence, intersectionality equips us to have a holistic, dignified, and nuanced response to people experiencing harm. Intersectionality is recognising and understanding how a person (or group of people) may have overlapping elements of their identity that create unique experiences of discrimination and disadvantage. The concept of intersectional disadvantage or discrimination is sometimes called “intersectionality”. It explains how people may experience overlapping forms of discrimination or disadvantage based on attributes such as Aboriginality; age; disability; ethnicity; gender identity; race; religion; and sexual orientation. Intersectionality recognises that the causes of disadvantage or discrimination do not exist independently, but intersect and overlap with gender inequality, magnifying the severity and frequency of the impacts while also raising barriers to support. For example, a woman who is transgender and comes from a non-white background could face discrimination for all three identities independently, as well as for the combination of all three identities. It is important to look at gender-based violence through the lens of intersectionality, which means addressing their other identities – for example their ethnicity, cultural background, class background, and disability, as well as their diverse gender and sexuality. The Australian Government – Workplace Gender Equity Agency (WGEA) provides further information about intersectionality and gender equity including: Sexual violence against Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women and children continues to be prevalent. Estimated prevalence data of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples who have experienced sexual violence are unreliable due to under reporting and non-disclosure of many victim-survivors. Recent figures show Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples are around 3 and a half times more likely to have been the victim of sexual assault compared to non-Indigenous Australians. Studies into the impact of sexual violence on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women and children indicates an association between sexual violence and poor mental health, suicide, incarceration, and diminished life opportunities and self-determination. According to Kyllie Cripps, author of Indigenous domestic and family violence, mental health and suicide (2003), Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (First Nations) people are overrepresented as both victim-survivors and perpetrators of family and domestic violence (that is, violence that occurs within family or intimate relationships). This situation arises when ‘people in positions of powerlessness, covertly or overtly direct their dissatisfaction inward toward each other, toward themselves, and toward those less powerful'. The Australian Government – Australian Institute for Health and Welfare (AIHW) has further information. LGBTIQ+ people are one of the most vulnerable sections of our community, not only more likely to experience sexual harm, domestic, and family violence but less likely to report, seek, and receive appropriate support and response. Data is limited but some research has shown that the rates of sexual, family, and intimate partner violence for LGBTQ+ people are statistically very similar to the rates reflected in general population data. Until recently, LGBTQ+ sexual harm, domestic and family violence was noticeably absent across many areas, including University frameworks, policy, response and prevention. Many LGBTQ+ people and communities have been impacted by a lack of visibility and support specific to their needs. Many do not know or feel they cannot trust that an inclusive service system response is available to them. UNE Ally Network is a group of staff and students who are committed to making the University of New England a welcoming and inclusive environment for members of the LGBTQIA+ community. A list of UNE Ally members can be accessed through the UNE Ally Network page where you can contact anyone on this list if you have any questions or concerns about being a member of the LGBTQIA+ community at the University of New England. Resources like Say it out Loud and acon are also good external sources of further information, support and advice. The Australian Government – Australian Institute for Health and Welfare (AIHW) also has further information. In Australia, violence is a serious and widespread problem. Although violence affects people from all cultures, ages and socio-economic groups, the extent, nature and impacts of violence are not evenly distributed across people and communities. People with disability experience violence and abuse at significantly higher rates than people without disability. There is increasing recognition that some people may be at heightened risk including women with disability, young people with disability, as well as people with intellectual and psychosocial disability. There is very little data collected in Australia that specifically addresses issues of neglect and exploitation. People who live with disability may experience additional barriers that make it difficult for them to make a disclosure or report. These circumstances may include reliance on support workers, physical and social isolation, a lack of information and understanding of what constitutes sexual harm, and communication difficulties. Fear of losing access to services, facing judgment upon making a disclosure or report, and fear of not being believed are additional factors that may prevent students from seeking support. Universities should ensure staff are provided with disability inclusion and awareness training to help identify and support students with disability. The Royal Commission into Violence, Abuse, Neglect and Exploitation of People with a Disability found that: The Australian Government – Australian Institute for Health and Welfare (AIHW) has further information.