In a case of palaeontological navel gazing, a new record for the oldest belly button has now been set, after a team of international scientists made a remarkable discovery on the 125 million-year-old fossilised skin of a dinosaur, Psittacosaurus – a distant cousin of Triceratops.

Dr Phil Bell from the University of New England (UNE) led the study, and says while it’s common for land animals to have umbilical scars for at least part of their life, until now, no evidence of a belly button had been found on any dinosaur.

“Psittacosaurus was a two-metre long, two-legged plant eater that lived in China during the Cretaceous period roughly 125 million years ago,” says Dr Bell. “This revelation gives us an intimate view into the life and appearance of the animal.”

Unlike human belly buttons, Psittacosaurus had a long scar along its belly surrounded by distinctive scales, which the researchers found was similar to some modern lizards and crocodiles.

Also unlike humans, dinosaurs did not have an umbilical cord due to the fact that they laid eggs. Instead, their yolk sac was directly attached to the body via the slit-like opening like other egg-laying land animals; it is this opening that seals shut around the time the animal hatches, leaving the distinctive umbilical scar.

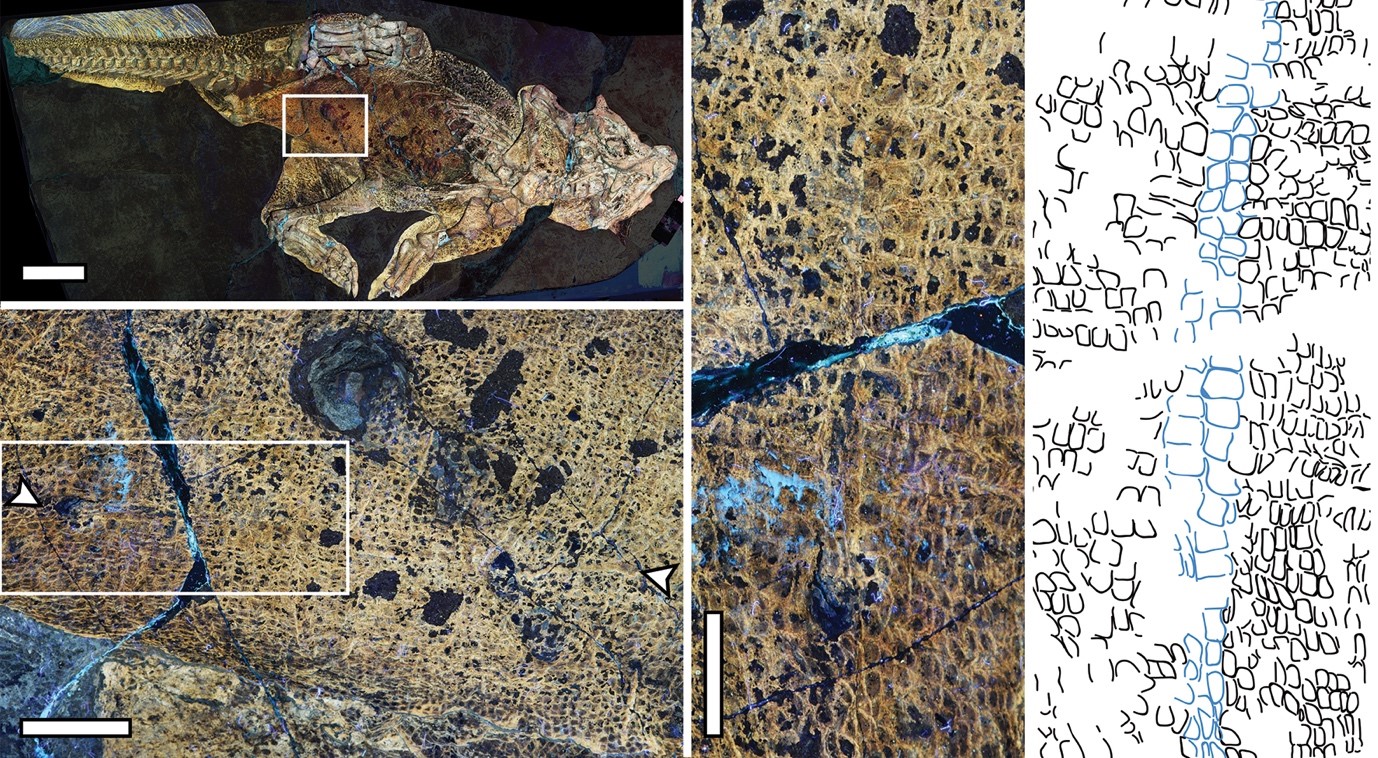

Image: The fossil of Psittacosaurus under laser fluorescence imaging showing the belly button, or umbilical scar. Inset shows close-up of the distinctive scales surrounding the umbilical scar, shown in blue in the line drawing.

The discovery was made while Dr Bell and his colleagues from Hong Kong, Belgium and the U.S. were studying what he describes as “the most important fossil we have for studying dinosaur skin.”

“The specimen is a superbly preserved skeleton that was found lying on its back, entirely covered in fossilised skin. The same specimen made news in 2021, when researchers revealed the appearance of its cloaca – the common opening for the genitals and digestive tract, which it shares with birds and reptiles.”

Co-author of the study, Dr Michael Pittman from the Chinese University of Hong Kong, says the research team used a new, ‘high-tech’ approach, which meant they could make out the scales that lined the umbilical scar, or belly button – a detail that would not have been picked up otherwise.

“Whilst this beautiful specimen has been a sensation since it was described in 2002, we have been able to study it in a whole new light using novel laser fluorescence imaging, which reveals the scales in incredible detail,” said Dr Pittman.

The study was published today in BMC Biology, and can be read here.