Our world is connected in subtle yet significant ways – which is why the fate of threatened tigers and snow leopards in the Himalayan kingdom of Bhutan may rest with a University of New England researcher.

Dr Phuntsho Thinley has returned to his homeland to embark on one of the most ambitious and exciting research projects his country has seen - to test whether fresh water quality in the eastern Himalayas depends on the presence of tigers and snow leopards. It has implications for nearly 1.75 million people in South Asia who rely directly and indirectly on Bhutan's river systems.

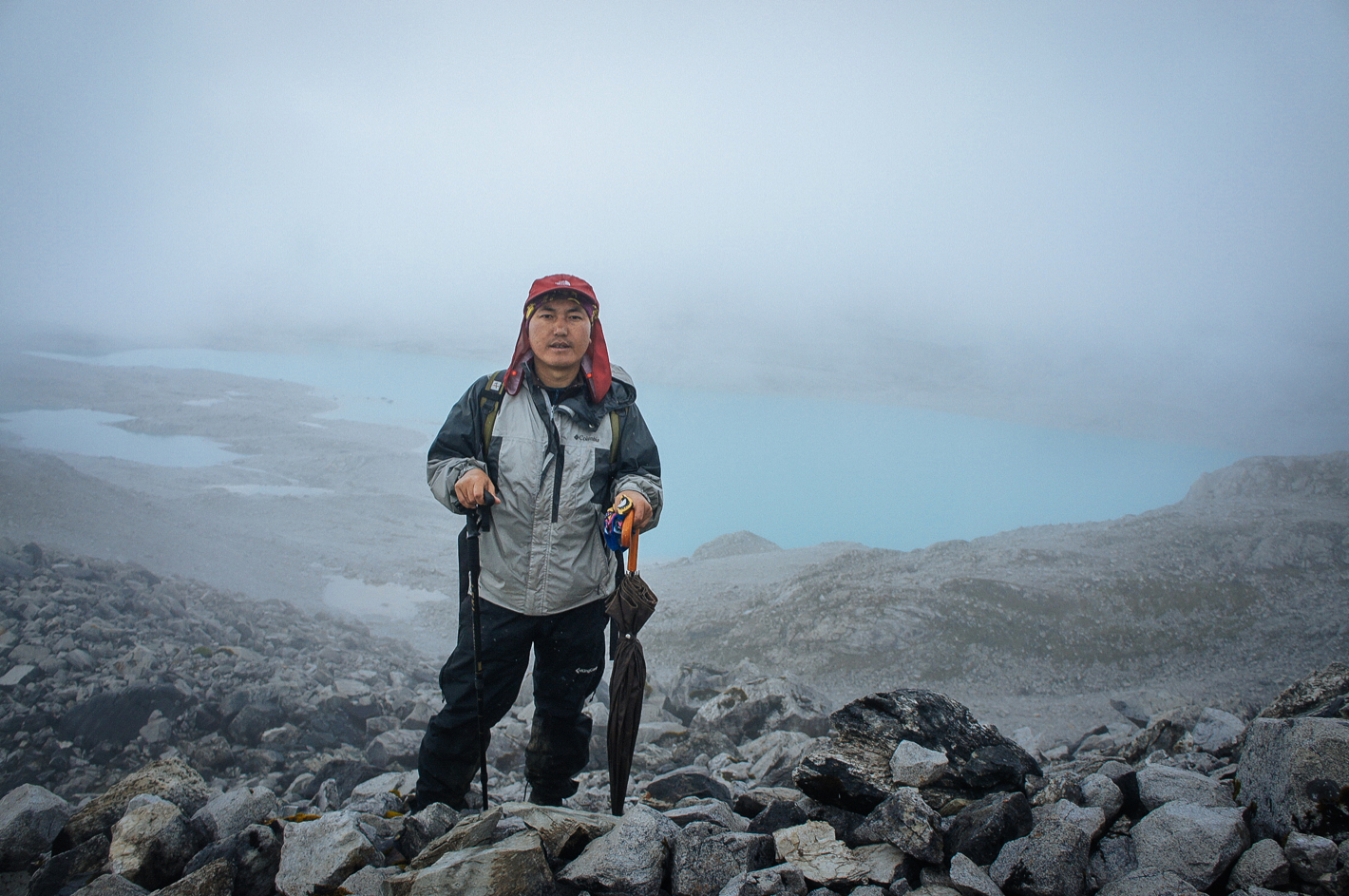

Phuntsho will spend a year trekking alpine meadows, cool temperate forests and rugged gorges evaluating whether the large predators living in the headwaters manage the number of herbivores that feed on the vegetation necessary for quality water downstream.

"If we have large carnivores in the catchment, do they control the herbivores so they don't over-graze and compact the soil, hampering water infiltration that recharges the water table?" asks Dr Thinley. "I'm looking at two catchments in the east and west of Bhutan that provide fresh drinking water for about half of Bhutan's people and the source of hydropower for many more, trying to determine what role tigers and leopards play in catchment hydrology and future climate change adaptation."

Only about 103 tigers and 96 snow leopards are thought to survive in the study region, and Phuntsho will compare catchments with and without the big cats. It's a region he knows well, having worked as the park superintendent of Jigme Dorji National Park and more latterly as the principal forestry research officer at the Ugyen Wangchuck Institute for Conservation and Environment Research.

"Without empirical evidence, we have no proof of how important tigers and snow leopards are ecologically," Phuntsho said. "If we can prove they benefit water infiltration and discharge, then this may provide a rationale for their conservation."

He is mostly trekking on horseback, measuring everything from rainwater infiltration and discharge rates to floral communities, leaf-litter thicknesses, soil characteristics and grazing regimes. Some of his more remote sites, at elevations as high as 5200 metres above sea level, take up to 21 days to reach.

However, try as he might, Phuntsho is not counting on seeing any tigers. "I have seen a snow leopard from a distance, but it's very hard to encounter a tiger; they have lots of thick forest to hide in," he said. "Seeing one is very auspicious; my people consider that a very good omen, but to even hear a tiger roar in the forest is a humbling experience."

Up until now, the big cats have been missing from much of Bhutan's landscape management. "I am going to change that mindset," Phuntsho said. "I expect to be making recommendations at many levels in terms of conserving tigers and snow leopards and managing their environments more effectively, so that we might move beyond seeing them as livelihood threats and instead recognise them as ecosystem service providers. My aim is to develop ecosystem models to sustain water yields in a changing climate."

At UNE, Phuntsho has had access to resources unavailable in Bhutan and the support of a multidisciplinary team with expertise in soil, ecology and hydrology. His colleague, Dr Karl Vernes, thinks the research will be invaluable. "Phuntsho is keen to get an education while studying something important to Bhutan, so that he can return and do better things in his own country," Karl said. "His landscape-wide approach may have applications for catchment management and species conservation elsewhere in the world."

Phuntsho's compatriots Tiger Sangay and Sangay Dorji have similarly studied subjects at UNE of pressing importance to Bhutan. Tiger is finishing a PhD on a migratory bovine species called the takin, having previously studied compensation schemes for farmers who have lost livestock to tigers for his Masters. Sangay has completed his undergraduate and Masters at UNE - on red pandas - and is close to finishing his PhD on the biological corridor network designed to protect species like the tiger.

"These projects have already made important contributions to policy and management in Bhutan," Karl said. "And like Phuntsho before them, Tiger and Sangay now work in influential roles and are among the top wildlife conservation researchers in their country."