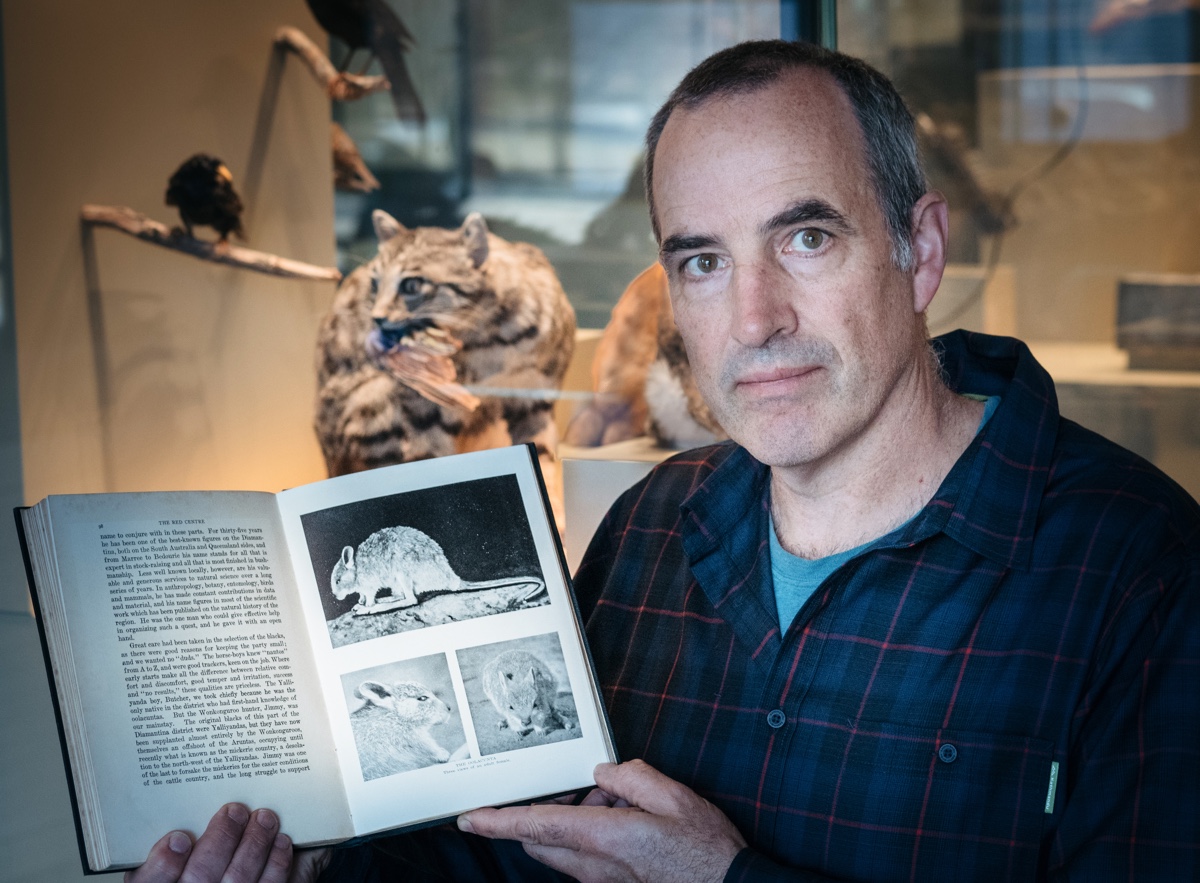

In late 2018, zoologist Karl Vernes mounted a crowdfunded expedition into Central Australia to find the long-vanished desert rat-kangaroo. He found cats.

And foxes, and rabbits, and unexpectedly, a pig. “It’s a feral landscape out there,” said Karl, a widely-published mammal expert and Associate Professor at the University of New England (UNE).

Disheartened but undeterred, Karl is next week joining an Australian Desert Expeditions camel team that will thrust deep into the Simpson Desert in another attempt to establish whether the rabbit-sized kangaroo still exists.

This time, Karl will be looking for signs of mikiri, Aboriginal wells dug down into the desert sandhills. The mikiri are likely now collapsed, but old records suggest that near some of these tiny hand-dug oases were Aboriginal middens containing the bones of the desert rat-kangaroo.

He is being supported in his camel-powered quest by the Mohamed bin Zayed Species Conservation Fund, which supports the preservation of endangered species.

"It's a long shot," Karl admits. "We have no guarantee of even finding a mikiri, and then we'll be looking for signs of an animal last known to science 84 years ago."

"But I'm hoping that this deep into the desert, there will be fewer foxes, and more chance that there's a pocket where the desert rat-kangaroo still persists."

Unfortunately, he expects that feral cats – sustained by the rabbits that live in the desert dunes – will still be present and predating the desert's small animals.

The desert rat-kangaroo is one of a suite of species in what has been described as the "critical weight range" for Australian mammal extinctions.

The phrase refers to animals that weigh between 35-5500 grams, which makes them ready prey for cats and foxes. Extinct or shrinking populations of marsupials like bilbies and bettongs fit into the critical weight range – and so does the "presumed extinct" desert rat-kangaroo.

If nothing else, Karl said, failure to find evidence of the desert rat-kangaroo will add support to the critical weight range theory.

As he returns from a fortnight in the desert, Karl will also collect another 47 camera traps that he set up in June at Goyder Lagoon, on the Birdsville Track in north-eastern South Australia, and analyse the images they have gathered.

The 50 camera traps set up in 2018 captured images mostly of feral cats and foxes. The scarce native animals that were photographed were largely of hopping mice and dunnarts (a mouse-like marsupial) and a single kowari, well outside its known range.

The desert rat-kangaroo has twice appeared and twice vanished from scientific view since the late 1800s, the last time in 1935.

Karl is hopeful that the little marsupial is still alive, “and that we’ll find it before it blinks out of existence”. But after reviewing the 2018 camera trap data he is a little less optimistic.

“Cats are known to have driven several small marsupials to extinction in the wild,” he said.

Back in his academic role at UNE, Karl is part of a $30 million UNE-led project aimed at managing Australia’s estimated 18 million feral cats.

“Every feral cat we remove from the landscape is a reprieve for the hundreds of small native animals that each cat eats each year."

"It’s important that we keep seeking answers for feral cat management, because apathy guarantees that Australia will only grow steadily more impoverished of small animals.”