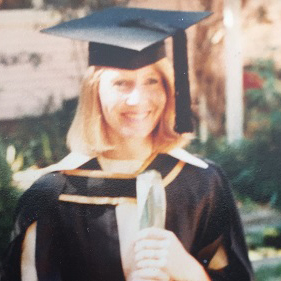

Vicki Poulter

A visionary educator and father remembered

One image springs immediately to Vicki Poulter's mind when asked to share memories of her father, legendary Professor Bill McClymont, from the time they shared at UNE.

"Dad always walked fast, wherever he went," she says. "I can remember one time being in the library and watching him literally flying between two buildings, his black academic gown flapping behind him. He was always so purposeful."

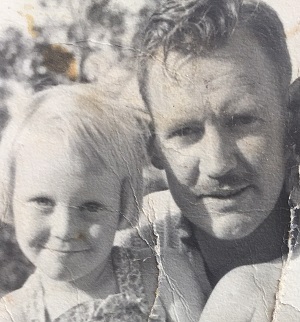

The eldest of Bill and Viv McClymont's four children, Vicki practically grew up on the university campus after the family moved to Armidale in 1955 for Bill to take up his appointment as the foundation dean of the Rural Science faculty. Its multi-disciplinary degree program was the first of its kind in Australia and it was just one year after UNE had become independent of the University of Sydney.

"I can remember going up to the Animal House with Dad and visiting CSIRO at Chiswick to look at sheep they were working with for nutrition research," Vicki says. "Driving around with Dad you'd be continually stopping so he could climb through fences and look at pastures. I knew that nutrition and pastures were really important for animal health from a young age."

Bill was an emerging leader in the field of nutritional physiology and had been documenting theories for "a third way" for some time, particularly in the Australian Veterinary Journal, when he came to the attention of UNE. "Dad considered that there was veterinary science for vets, agricultural science for plants and soils, but nothing integrating the soils, plants, animal husbandry and livestock production," Vicki says. "His inaugural lecture was titled All Flesh is Grass."

For a time she looked like following her parents into science, before Vicki found her niche in the Arts at UNE, studying biological sciences, geography, sociology and education. But her less formal education, with her dearly loved parents, had started years before.

"All Mum and Dad's friends were academics; they were all the people I knew and grew up with," she says. "UNE was a bit like Camelot in those days; it was small and had a wonderful atmosphere. Later, when I was doing zoology and botany, the demonstrators in our prac courses included some of Mum’s fellow scientist wives."

It was the late 1960s by then and the world was awash with anti-Vietnam War protests. "It was an extraordinary time to be at university, especially given I was a folk singer," Vicki says. "Mum and Dad always encouraged us to look at the big picture; I'd been trained as an activist from a very early age."

Meanwhile, her father Bill was cementing his reputation as a visionary educator, committed to teaching what he called agro-ecology. The Rural Science faculty was, Vicki says, "a shining beacon for the university and its students were really inspired, seeing themselves as very special to be doing this prestigious course".

"Dad was such a hero," she says. "In my horsey days, growing up and going to shows and meeting lots of farmers, everywhere I went people praised Dad as someone who called a spade a spade. He was so loved and admired because he did a lot of extension work and would actually listen to those living close to the soil. He and Professor Jack Lewis would get into a uni Holden and drive all around NSW giving talks to farmers.

"But I think Dad was at least 50 years ahead of his time, in thinking about the farm as a complete system. He believed you needed to understand the whole before you could specialise. His Rural Science graduates from the early 1960s and '70s were in demand all over the world because they were broad thinkers and could put any problem into context. Dad was very critical of the cult of the expert in a narrow field and the damage they could do without considering the ecology of the whole."

After further studies herself in Communications, Linguistics and French, Vicki travelled the world, gaining a broad education. Setting up her own interior design business enabled her to work from home while her children were young.

But watching both her parents suffer from chronic diseases at the end of their lives had a profound impact. Vicki began her own research journey into human health and nutrition, which soon took her "back to Dad's stuff" - the idea that all plant, animal and human health starts with the health of the soil. She started questioning traditional dietary advice, founded the Weston A Price Foundation in Australia and that morphed into Nourishing Australia, which encourages people to think about the food they eat, its effect on their health and that of the planet. She now also works as a food coach, helping people to make healthier choices.

When I first questioned the food pyramid, put together by vested interests, I was treated like a fruit cake," Vicki says. "But Dad always taught us to think critically and to never be afraid to challenge conventional dogma; he always said you need to drink from the running stream, not the stagnant pond. I'm now part of a fantastic regenerative agriculture network around Australia and globally. The good farmers are out there following the ecological principles that Dad espoused.

The purchase of a 40-hectare farm 13 years ago at Hampton, near Oberon ("high and cold, like Armidale"), enabled Vicki and her husband Tim to apply holistic land management on a small scale, raising cattle and growing garlic. A passion for regenerative agriculture was perhaps written in her DNA.

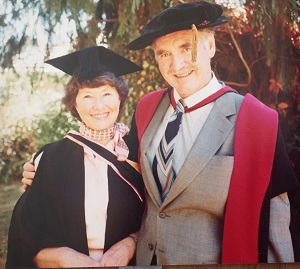

The move towards specialisation in the degree and what Vicki describes as "academic empire building" had spelled the end of Bill's 21-year deanship at UNE by 1976, but he continued to consult internationally, including for the World Bank and the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations."Almost up until the time he died in 2000 he was still writing and honing his famous flowchart on agro-ecology," Vicki says. "He was a very special person and he and Mum were an amazing couple. You should have seen them on the dance floor."

In academic circles Bill is remembered as a giant intellect, renowned for his forthright ideas, as the author of the perpetual pentagram (about the inter-relationships between evolution, ecology, economics, ethics and education) and widely regarded as a father of the modern-day regenerative agricultural practices that Vicki has adopted.

To her, Bill McClymont was a devoted Dad, a renaissance man and great gardener, who "opened up the world", took his family bushwalking, camping and fishing, loved art, music and singing in the UNE choir, relished words and writing, and captivated his children with adventurous bedtime stories about a country boy called Jimmy.